Lovely bubbly – the art of controlling air bubbles in glass

Jo Mitchell has melded the materiality of glass and the immateriality of the air bubble to create art that investigates ‘humanness’ and identity. Here she explains how technology has enabled her to push the boundaries of her practice in this interview with Glass Network digital editor, Linda Banks.

You have a varied background in glass. How did you get started on your journey in glass?

I studied for a bachelor’s degree in Three-Dimensional Design at Manchester Metropolitan University. It was a materials-based, multi-disciplinary course, which I loved. I got to work with wood, metal, ceramics, glass and other materials. I was captivated by the hot glass process and the immediacy and beauty of the material. Glass has had a hold on me ever since in its many forms and means of production; I’ve never exhausted my interest in it!

I specialised in hot glass and metal for my BA, graduating in 2000. I then went on to do an MA scholarship in glass design for production through Wolverhampton University and Edinburgh Crystal, and worked as a glassware designer, before leaving to set up my own studio practice making glass art.

My own practice started with blown and cold-worked glass vessels, which I sold through galleries and art fairs, alongside freelance design. Then I began to move into kiln forming. I set up a second studio business, Juo Ltd, with glass artist Jessamy Kelly, who I met during my time as a designer for Edinburgh Crystal. We worked together for six years, making contemporary fused glass panels and installations for domestic and corporate interiors. We completed projects for the NHS, among others, and our work for Newcastle Building Society won the Pearsons Prize in 2008.

I started a part-time PhD at the University of Sunderland in 2009 and my personal practice was transformed when I began to explore ways of controlling air bubbles in glass using kiln-forming, digital and waterjet technologies.

How did your PhD research transform your approach to glass?

The PhD gave me the impetus and access to facilities to experiment with new technologies, such as waterjet cutting and digital stencil making, that weren’t as readily available to me in my studio. My premise for the research was that, if air entrapment could be controlled in glassblowing to a level of detail to create images (as in the Ariel technique – a Swedish method to control the shape and positioning of air bubbles in blown glass for decoration), it must be possible to make similar controlled bubble forms, as text, imagery and 3D forms, in kiln-formed glass, as well as to make the process repeatable and transferable to different types of glass formats and kilns.

The waterjet process is provided by a CNC machine that is programmed using computer-aided design (CAD) software. It cuts through glass sheets using a high pressure (30-60,000psi) jet of water mixed with abrasive, such as garnet. This kit is used regularly in the automotive industry and can pierce through glass and cut detailed shapes at a speed and precision that isn’t possible by hand.

The research was technically challenging and there were many ups and downs over the course of six years of study. It required a huge amount of perseverance and there were a lot of failures. Balancing self-employment and research was demanding, but it was during my PhD that I found my creative direction. Technically and conceptually, my work began to come together. A PhD is quite a solitary experience but, with the enthusiasm of the mechanical engineers and the technical assistance at Sunderland, I was able to push the boundaries of what was possible in controlled bubbles with new successful techniques for precision air entrapment in the kiln.

The intense period of study, reflection and experimentation also gave me the focus to express myself artistically in a more meaningful and individual way than I had previously. I completed my PhD, ‘Precision Air Entrapment through Applied Digital and Kiln Technologies: a New Technique in Glass Art’, in 2015, two weeks before the birth of my first daughter. Since then I’ve been developing the many ideas I have for artworks using this technique. I also work part-time as Waterjet Technician at the University of Sunderland. I enjoy the university environment.

Can you tell us something about your innovative cast glass work that captures and controls air bubbles?

I was excited by the idea of controlling air entrapments as internal forms in glass. I’ve always been mesmerised by transparent glass’s internal dimension. The inner space of glass with air suspended in it seemed to me to have so much creative potential.

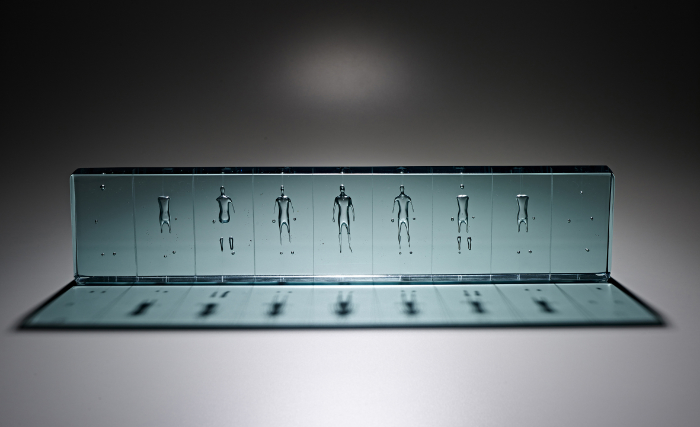

The integration of the techniques of CAD software, waterjet cutting and kiln casting and fusing techniques with the clarity and thickness of float glass opened up the possibilities for scale and depth of the artworks themselves. This allowed multiple cut-through layers and intricate 3D forms of air entrapments within solid sculptures that weren’t previously possible before access to digital technologies.

To make the pieces, multiple waterjet-cut layers are built up in between plain sheets of glass and surrounded by dams or a mould. The stack is heated carefully in the kiln to squeeze out excess air and evenly fuse the layers until the bubbles form in the cut-outs. The kiln program is dictated by the size of the air-void, the type and thickness of glass and the size of the piece. When the bubbles form, the piece is crash cooled and annealed for between days and weeks, depending on its size. Each one usually necessitates several test versions, as any change to the bubble size or type of glass requires moderations to the firing cycle.

What are the themes behind your work?

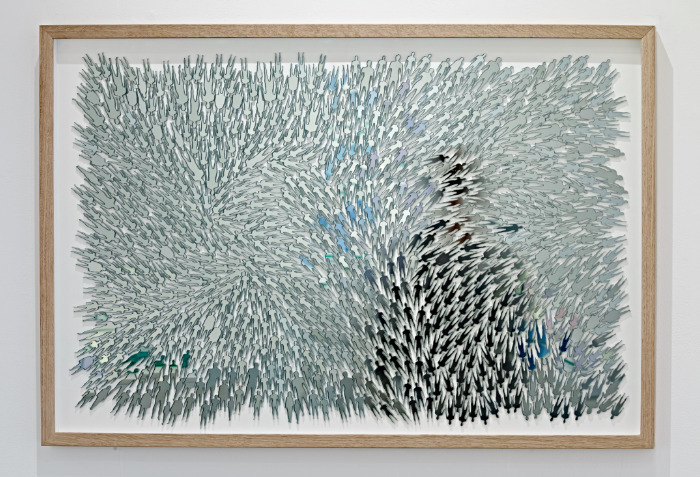

When air becomes the ‘medium’, it is much like glass: transparent; it contains space, yet it can be the form itself. It has such power to create metaphor: presence, absence, transience, emptiness, anonymity, ambiguity.

I became interested in using the human form as a suspended ‘entity’ in the interior of the glass itself, to explore these metaphorical connections to the human condition. So the theme is existential: the air figure became a symbol for the immaterial ‘self’ – the space which contains our identities as individuals and the perception of ourselves within the collective.

Playing with the heat of the kiln to alter the characteristics of the air figure allowed me to explore what remains when the human identifiers are diminished or removed, both physically, in the piece, and metaphorically. I’m interested in the paradox of emotional connection and detachment that we can have for others in society. Connectedness and isolation are themes that I return to.

How do you use technology in your glass practice?

Technology for me isn’t the specific aim in itself. I like to learn or adapt technologies – new or old – that assist me to reach where I want to be creatively, or to develop avenues for new work that might have been difficult, or unachievable, before. Advances in technology add to the creative’s toolkit!

What are your thoughts on water jet technology?

Freedom and frustration! It is another tool which can produce amazing results. However precision technology can also be temperamental and, like any technique in glassmaking, it requires a level of understanding of the process. For me, it opened up avenues for making artworks that were previously impossible. Having access to ‘play’ with new technologies – merging creative, industrial and scientific know-how – creates the space for innovation.

What is your favourite creation and why?

My latest piece is usually my favourite because it is taking the work to the next step.

Who or what inspires you?

I don’t think there is a particular person or thing that inspires me as such, but inspiration usually comes when I have headspace – in that meditative place: quiet time in my studio, driving, listening to music, or even in the ‘zone’ of cold-working! I also get inspired listening to people talk with passion about what they do, whatever it is. Being around creativity and hearing people speak at glass conferences, like those of the CGS or the Biennale, always brings back that creative buzz.

What are your career highlights?

I think travelling and meeting like-minded people though my work has been a highlight. I’ve been fortunate to visit and exhibit in America several times. Most recently I went to Pittsburgh Glass Centre, where my work was part of a fantastic exhibition of glass art and technology, and met some inspiring artists who are pushing the boundaries of innovation in glass.

I’ve taken part in a UK design exchange with French designers in St. Etienne, as well as visiting Poland and the Czech Republic with Edinburgh Crystal to source production facilities. A definite highlight was going to Pilchuck during my PhD with support from Sunderland University’s Futures Fund and working as technical assistant to Keke Cribbs. I met Dale Chihuly there and watched his team work.

Also, having my work bought for the permanent collections of the National Glass Centre, Shanghai Museum of Glass and Alexander Tutsek-Stiftung Foundation, and purchased by collectors, is wonderful.

How has COVID-19 impacted your practice?

When the first lockdown hit, I’d just returned from the opening of the exhibition of glass and technology in Pittsburgh, USA. The exhibition was open for a week before Pittsburgh was locked down. It was a shame because six months of hard work had gone into making new pieces for the show. Although it had an online presence, it was disappointing. But at least we had the opening.

During lockdown, I wasn’t able to work in my studio as I was at home looking after my daughter. Finding time and headspace to be creative during lockdown was practically impossible and I didn’t make any new work. I was fortunate that, for the two days per week that I work for the University/NGC, I was furloughed, making the situation easier for me than I’m sure it has been for a lot of artists.

People have commented to me that the air entrapment figures resonate with the isolation of current times and that new perspective is interesting. I think new work will come out of this period eventually.

An unexpected outcome of my research has been connecting with academics outside of the arts who are interested in my methods of precision air bubble control in glass. I’m collaborating with Volcanology researchers in the Earth Sciences Department at Durham University to investigate how bubbles develop in volcanic magma in comparison to glass – an exciting departure!

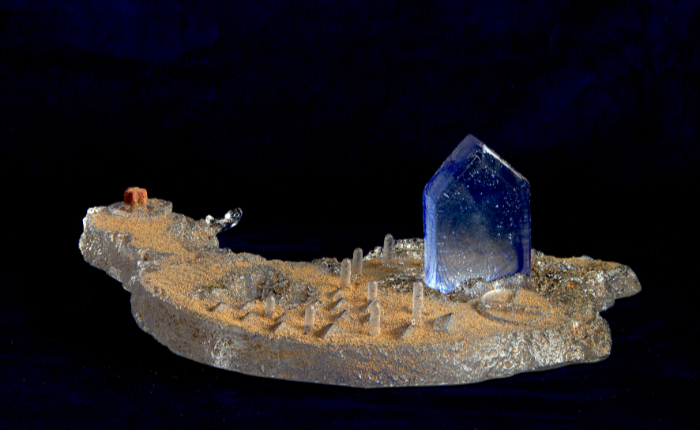

Main feature image: Deconstructed Being II (2019). Photo: David Lawson.

About the Artist

Dr Jo Mitchell studied at Manchester Metropolitan University before completing an MA Scholarship as a designer to Edinburgh Crystal in 2001. She set up her artistic practice in 2003. Jo undertook a PhD at the University of Sunderland, where she developed an innovative method of controlling air in glass artworks. The research had a transforming influence on her work and took her love of the material’s transparency, form and balance towards a highly sculptural sensibility. She has exhibited internationally, and her work is in the collections of the Shanghai Museum of Glass, National Glass Centre, UK, and the Alexander Tutsek-Stiftung Foundation, Germany. She sells her work through exhibitions or direct from her studio. Find out more via her website: www.jomitchellglass.com