Beyond the slides – looking into Europe

Katharine Coleman MBE, revered glass engraver and member of the Contemporary Glass Society’s (CGS) board, shows us how much the art world has changed since the organisation was established and puts the case for greater collaboration with glass artists from across the European continent.

Hooray! This year the CGS New Graduate Review magazine will invite applications from glass course graduates at colleges throughout Europe for the first time. As a CGS board member I am delighted that CGS is now looking farther afield for members and participants in its many activities – maybe soon even beyond the constraints of geographical Europe.

Looking back

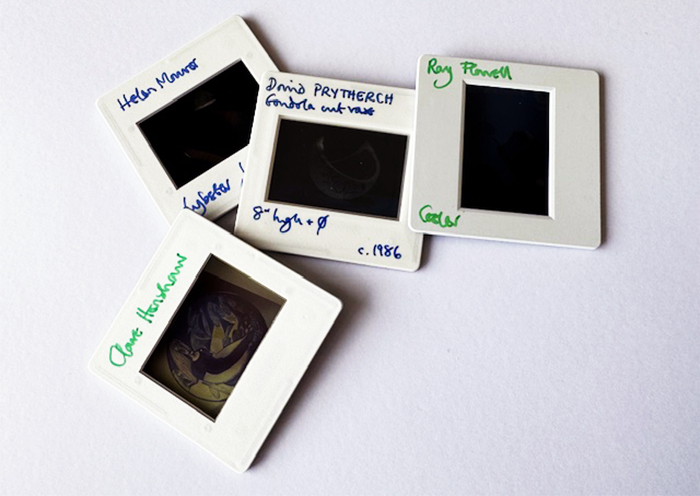

When CGS was founded 28 years ago, mobile phones were in their infancy and if one submitted an image to a gallery or exhibition, it had to be as a 35mm slide or transparency (see the picture, for the very young!)

Seeing others’ work was limited to visiting exhibitions and obtaining access to printed material. A duplicate slide cost some £10 to £15. Galleries seldom returned them. Conferences were particularly popular as it gave so many of us a chance to see a wider range of other artists’ work. Conference talks were peppered with interruptions caused by clattering slides falling out of the projector, or slides accidentally being placed in the carousel upside down – the subject of great frustration and much merriment.

It was hard to show work in galleries if one didn’t have a degree from a university glass course or images to show the gallery. It was expensive to send galleries slides speculatively, so first I would ring them to ask if they would like to see my glass. The conversation would go as follows: “Oh hello, I wonder if you would be interested in showing or selling my work?”; “Well, possibly, who are you?”; “Katharine Coleman”; “Never heard of you or seen your work. Were you at the Royal College?”; “No.”; “Any other glass courses? Which college?”; “Morley College.”; “Never heard of it – what sort of work do you do?”; “I’m a glass engraver.” At that point the phone went down – EVERYWHERE – except at Art in Action, near Waterperry, Oxfordshire. My lucky break came when I was shortlisted for the 2003 Jerwood Prize for Glass. Few of us had such lucky breaks.

Without Facebook or Instagram to promote our work, and without online banking, it was very tough selling work too! Hiring a MEPOS ‘card swiper’ cost over £500 for a week at Chelsea Craft Fair or Art in Action. Banking was a headache and insurance was expensive.

Now, in 2025, we have more of a chance with our images – wonderful, digital imagery, with the concomitant joys of Adobe for cropping, correcting blur, contrast and faulty focus, superb camera lighting and easy, free internet for sending images all over the world. There is now such a gulf between that age of slides and print and our age of digital images, PowerPoint, the internet, Facebook, Instagram and Zoom.

This gulf is occasionally apparent when work alarmingly like that of the 1990s appears in international exhibitions (as happened at the last Coburg Prize for Contemporary Glass), with jurists sufficiently young that they are not familiar with pre-digital images and reference books on glass from the previous two decades are seldom consulted. Helen Maurer won the Jerwood Prize: Glass in 2003 with glass objects placed on an overhead projector to produce magical scenes above them. Then the Third Prize at Coburg in 2022 went to an artist placing glass on overhead projectors with the images thrown onto the wall behind them. But we should agree that all things are cyclical.

Back in the day, the printed CGS Glass Network journals and the chance to attend conferences made the world of contemporary glass accessible to us new faces. At its first conference at Wolverhampton University, there was a debate about whom the CGS would be for. A well-established glass artist stood up and declared, “We want this society to be for professionals and not all these aspiring artists who are such a pain!” This comment made me shrink with shame as an aspiring artist myself. Thankfully that idea was not taken up. These early conferences were held alongside selected exhibitions and were very well attended.

Now, the expense of taking part in CGS activities is spread more lightly and fairly, with digital imagery, online exhibitions and talks. The double whammy of CGS losing its Arts Council grant in 2012, together with the ever-increasing postage rates, undermined the frequent production of the printed catalogues and membership growth slowed. However, we were saved by the CGS website and, later, the wonderful CGS Zooms that kept us in touch and diverted with regular talks through the miserable years of COVID-19, that helped raise membership numbers. With access to Zoom, meetings no longer require committee members to travel to London at great time and expense. In addition, members can submit images for most exhibitions at no expense, making participation in CGS affordable for all, and the internet has opened up a wider world generally.

Collaboration across Europe

Contact with other European glass artists is vital for the exchange of ideas and technical advice. Many CGS members have attended courses at the Summer Academies at Bild-Werk Frauenau in Bavaria, either as teachers or as students and, through this melting pot, we have made many contacts and firm friends outside the UK. Other CGS members have participated in the Coburg, and other, glass prizes, or shown their work in galleries in the Netherlands and France, though these are fewer in number. Each of these brings the opportunity to extend the network that CGS provides. There is a Dutch glass society, but here in the UK I believe we are the envy of most European artists for the support and stimulation that come from membership of CGS.

The decline in numbers of glass courses at universities here in the UK over the last 15 years alongside the decline of student numbers at glass colleges in mainland Europe is becoming seriously worrying. Minority crafts, such as glass engraving, are shrinking so fast that wheel engraving is now on the Heritage Crafts Red List of Endangered Crafts.

I teach short courses occasionally at Corning Museum of Glass in the US, at Bild-Werk Frauenau and at the glass school at La Granja, near Segovia in Spain. It helps to speak both languages well enough to teach, especially in Spain, where the students have little to no English.

In 2013 three of us glass engravers met at Bild-Werk Frauenau (Wilhelm Vernim, Norbert Kalthoff and I) and we were bemoaning the shrinking number of engraving students and classes in glass colleges throughout Europe. We decided to do something about it and invited engravers, teachers and gallerists from Germany, Czechia, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, UK, Poland, Estonia, Romania and Finland to a meeting at Bild-Werk that same autumn. This resulted in the formation of a Facebook-based international collective, called the Glass Engraving Network.

Without a committee, anyone in the network can organise an exhibition. Our first, in 2015, was ‘Gravur on Tour’, a selected touring exhibition of glass museums, which was small enough to pack into a large white hire van that was unpacked and supervised by a group of the participating engravers in each host country: UK (Stourbridge), Belgium (Lommel), Netherlands (Epe), Germany (Rheinbach Glasfachschule, where we held a week-long workshop with the top year in all aspects of cutting and engraving), Czechia (Kamenicky Senov), Estonia (Talinn, hosted by Mare Saare, Professor of Glass at the university), Finland (Riihimaki) and back to Germany’s Bild-Werk Frauenau, with an exhibition and conference at the museum there. The museum directors supervised the selection of the work so the exhibition avoided being dominated by a particular group. The museums were delighted that we produced a high quality bi-lingual (German and English) catalogue, sponsored by advertising, which they could sell alongside our work, and that their galleries were filled with an excellent, ready-made show for two or three months, allowing their staff a break. Sold work was replaced between stages.

Uta Lauren, the curator of the Finnish National Glass Museum just north of Helsinki at Riihimaki, was very supportive, saying she was keen to show Finnish glass students that “Glass engraving wasn’t just something nasty that the Swedes do!” (sic), so, before our show, we were sponsored to give 10 students several months’ intensive glass engraving tuition. They took to it like proverbial ducks to water. We also have contact with many international artists in South America, Australia, New Zealand, Japan – almost every country where contemporary glass engraving is known.

In 2019 we returned to Riihimaki with another ‘Back on Tour’ show. Dr Sven Hauschke , Director of the Veste Coburg in Germany had been so impressed by the quality and energy of our show that in early 2020 he shipped the entire exhibition of 150 pieces to the European Museum of Contemporary Glass at Roedenthal. The show opened in mid-March 2020, just one day before COVID-19 forced the museum to close for over a year, so nobody ever saw our show. A touring show of Spain and France was similarly abandoned the following year and it has taken time to get things going again. Planning and organising these shows takes a good year, so our next exhibition opened in 2023 in the North-Rhine Westphalian Industrial Glass Museum at Gernheim on the River Weser (famous for the Pied Piper and nearby Hamelin). With a glass cone, built as a copy of the Stourbridge cones in 1826 with a surrounding village, Gernheim still makes glass in the cone and runs courses alongside the museum. Our exhibition filled the ‘Old Master’s House’.

We are struggling to show work beyond Germany but, as we regain our post-COVID-19 momentum, our current exhibition is being hosted by the beautiful glass museum at Coesfeld-Lette, not far from Hannover. If you are not familiar with the Ernsting Stiftung Museum at Coesfeld, it is well worth a visit as it hosts the best (and best displayed) collection of Middle and West European studio glass in Europe. The Ernsting family made their fortune in affordable clothing and spent their fortune since 1945 – and continue to do so – on modern glass.

Google Translate is our great communication tool. Despite Brexit, English has replaced French as the lingua franca of modern Europe and European glass and I hope that Brexit and our separation from Europe will soon be a regrettable few years in the past. In 2002, before Czechia became part of the European Union, it was possible to attend symposia to show work and meet engravers from all over Europe, including Russia; my poor, but just adequate, Russian (learned to welcome my son-in-law’s family to his wedding in 2000) allowed us to chat and make good friends. There are some astonishingly gifted artists there, including portrait artist Alexander Fokin, grandson of the famous ballet choreographer. My contact with them continues, despite recent history, and in May 2020 I was invited to a conference at St Petersburg hosted by the State Glass Museum and the Hermitage to give a talk about West European contemporary glass – sadly another event cancelled by COVID-19.

I hope the invitation to European graduates in the next CGS New Graduate Review will encourage CGS to consider following the Glass Engraving Network’s example and start exhibiting pan-European work in significant museums. Online exhibitions are great, but nothing beats real exhibitions and real exhibitions lead to sales and contact with the outside world. There are more collectors in Europe than the UK.

Sarah Brown, Chair of CGS, concurs with this idea, and the CGS Team aims to push the exhibition possibilities into Europe and beyond. Sarah says, “Our main aim is to elevate and promote the amazing glass produced by our members, building new networks across the world and educating the next generation of glass makers in the infinite creative possibilities that this incredible medium offers.”

This year, I hope there will be graduates from Ukraine, Moscow and St Petersburg joining in with applications for the New Graduate Review, and just as many graduates from Romania, Bulgaria, Slovenia, and of course all the more familiar European countries with glass courses, now that applications via the internet can fly above and beyond political barriers. Good luck to you all! It’s the chance to build a new generation of friends.

Find out more about Katharine Coleman MBE and her work here.

Main feature image: Degree students – surprisingly happy – at the end of my intensive month’s course in cutting and engraving, part of their first degree. Taken in 2009 at Escuela de los Vidrios, San Ildefonso de La Granja, Spain.