Capturing history: Glass Ships in Bottles exhibition

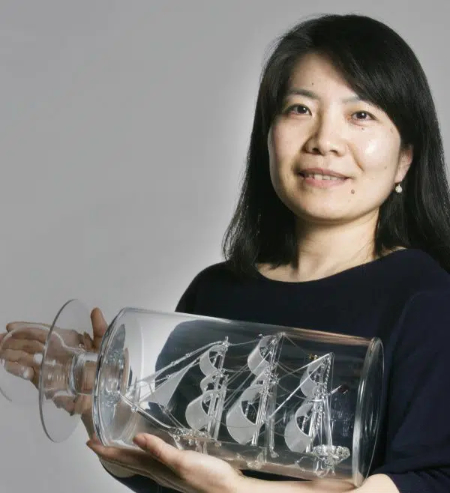

Glass artist and researcher Ayako Tani has curated an exhibition of over 150 glass ships in bottles, and new glass artworks, at the Scottish Maritime Museum in Irvine. Emma Park explains the history of these vessels and describes some of the modern pieces that have been inspired by this craft.

This exhibition, curated by the Japanese glass artist Ayako Tani, explores the history of glass ships in bottles produced in Britain in the last century. It is based on her research project and book, Vessels of Memory: Glass Ships in Bottles (2018). Tani moved to the UK in 2006 from Tokyo, where she was a consulting engineer for a computer firm, to study glassblowing at the University of Sunderland. “I think it helps to move places if you want to change career so drastically,” she says.

In 2014, when she had just completed her PhD in Glass Art, she began to work with Brian Jones and Norman Veitch, two scientific glassblowers who had once worked at James A. Jobling Ltd, the former Pyrex company, in Sunderland. The pair later established Wearside Glass Sculptures, which became the first tenant of the National Glass Centre.

While working with Jones and Veitch, Tani’s interest was piqued by the glass ships in bottles that were scattered around their studio. She later found out that “they used to make thousands of ships in bottles”. Further investigation revealed that this was a craft which had had few written records, and whose traditions were passed down largely by word of mouth.

She also discovered that glass ships in bottles could be purchased for almost nothing on eBay, at car boot sales or in junk shops, despite the high level of “training and commitment” needed to create them. “It was upsetting in one way, because they should have more value,” Tani explains.

The objects displayed in this exhibition are largely from Tani’s private collection, which she has amassed since 2014, in an effort to preserve their legacy and the memory of the craft for future generations.

In 1972, Jobling began to lay off its staff. Among the first to go were the scientific glassblowers, specialists in using their lampworking skills to make laboratory equipment from the borosilicate glass trademarked as Pyrex.

Jobling’s Laboratory Division closed completely in 1982. Its former employees applied their skills to making small-scale, decorative pieces from the same type of glass, including leftover pipes from the factories. A common motif of these pieces was the enclosure of one object within another: a silver sixpence within a duck, a ‘pig within a pig within a pig’, and glass ships in bottles. Whimsical pieces like this had been made since Jobling had introduced Pyrex to Britain, after acquiring the production licence in 1921 from Corning Ltd in the USA.

These pieces had been made as a form of relaxation for scientific glassblowers in their spare time. However, in the 1980s, glass ships in bottles became so popular that their manufacture provided the glassblowers with a livelihood into the 1990s and early 2000s.

Sunderland became the leading producer of glass ships in bottles, thanks to its history of scientific glassblowing. Commercial production may have started earlier elsewhere, however. For example, in Hampshire, Lymington Glass Mystiques produced luxury models in the 1970s and 1980s, some of which were sold in the flagship department store, Harrods. Ships like these required a high degree of skill, and it could take a day or more to produce one.

Other centres of glass ship production included Lichfield and Dudley, in the Stourbridge area, as well as Sudbury and Winchester. It is uncertain when the earliest model was made, but it cannot have been before the introduction of borosilicate glass in the 1920s.

As the exhibition shows, the types of ships produced were usually famous vessels, or types of vessel from history, such as the Golden Hind, Santa Maria, Cutty Sark, a ‘Portuguese Man O’War’ or a ‘Viking Longship’. The name was often engraved on a little bronze plate affixed to a wooden display stand.

The vessels were usually made from clear glass. Occasionally parts of the ship, such as the sails, were made of monochrome coloured glass in yellow, amber or pink. Sometimes they were very detailed in the types of sails and arrangement of the rigging. There was also a range in the shapes and sizes of bottles, which could be displayed on their side or upright, and cylindrical or like bell jars or decanters.

While some glassblowers produced precise and time-consuming models, in 1984 Mayflower Glass, in East Boldon, started mass-producing small-scale models of its namesake ship. It expanded to the point where it was turning out 10,000 Mayflowers a week. There was a predictable loss in quality, with a once individualistic craft being turned into a production line. Prices were slashed, and other makers of the models could not compete.

In 2005, Mayflower Glass shut down its British factory and moved its operations out to Yancheng in eastern China. This effectively marked the end of the production of glass ships in bottles in the UK. With the saturation of the market, even the Chinese factory has now largely scaled down its business. In 2017, scientific glassblowing was added to the red list of endangered crafts by the Heritage Crafts Association.

This decline gives greater urgency to Tani’s project, which celebrates a craft that is now on the verge of extinction. She has exhibited some of her collection previously, at the National Glass Centre and elsewhere. New to this exhibition, however, are some of the early models from Lymington, as well as a collection of laboratory vessels lent by the scientific glassblower Paul Le Pinnet.

Tani’s own lampworked sculptures form one of the most interesting parts of her exhibition. One of these is City of Adelaide (see main feature image), an exquisite glass ship in a bottle modelled on a famous nineteenth-century clipper, which she made as a homage to Sunderland’s former shipping industry. Two lampworked sculptures enclosed in clear elliptical vessels, one of a flock of albatrosses and the other a lighthouse, present variations on the title theme. “I wanted to demonstrate that you can put any sculpture inside a glass bottle,” she states.

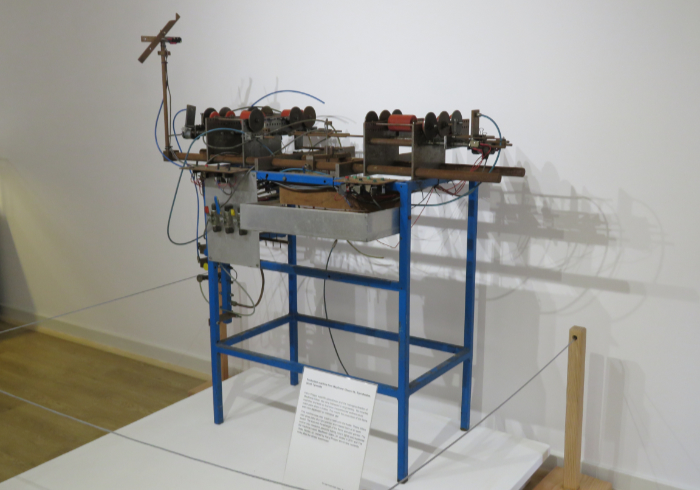

There is also Murmuration (2021), an arrangement of laboratory-style tubes which have been indented and coloured black to create a pattern that echoes both the line of migrating birds in the sky and the sweep of the calligraphic brush, capturing the spontaneous movement common to both.

The most striking exhibit in this section is Hysil: Blossom (2021). This consists of a salvaged laboratory phial manufactured with hysil glass, a material similar to Pyrex, which is clamped to a tall stand. Through the phial, a delicate branch with sprouting purple plum blossoms seems to grow organically. “I feel really nostalgic when I see or think about plum trees,” says Tani. For her, the blossom evokes memories of the end of winter in Japan, once encapsulated in a poem by the tenth-century scholar Sugawara no Michizane.

In its own way, each of these pieces reflects Tani’s experience as curator, collector and glass artist, connecting her appreciation of lampworking and its history with her memories of Japan. She previously explored related themes in her doctorate, in which she developed the idea of ‘calligraphic lampworking’, using molten borosilicate glass as if it were ink, to draw Japanese and Roman characters. In the future, she hopes to explore the theme of memory further, in a darker project on the Fukushima nuclear disaster and its damaging effect on the ocean.

The exhibition poses questions that Tani herself has not yet answered. One question is why these glass ships in bottles were, for a brief period, so popular; another is who bought them. The idea of the glass ship-in-a-bottle was clearly influenced by the much older craft of making ships out of wood and parchment and sealing them in whisky bottles, but what the connection is, as well as how the move was made from one to the other, has yet to be explored. While the wooden ships were made by real sailors, the scientific glassblowers had no specific connection with the sea, making their glass ships doubly artificial.

Tani’s investigations also suggest that glass ships in bottles were, for unknown reasons, much more popular in the UK than in other countries. Perhaps it says something about the British public’s long love affair with the sea, or with the paradox of having a vessel representing the freedom of the voyage enclosed, as if impossibly, in a vessel of a more prosaic sort.

Whatever the explanation, Tani should be commended for rescuing these unusual products of Britain’s lampworking tradition, telling their story, and drawing inspiration from them to create her own imaginative sculptures. In doing so, she has breathed fresh life into a fragile craft.

Exhibition details:

The Glass Ships in Bottles exhibition is on now until 9 January 2022 at the Scottish Maritime Museum in Irvine. It includes ‘Vessels in Memory’, an oral history and art project featuring filmed conversations with former scientific glassblowers who describe their work.

Also on show are brand new artworks by Ayako Tani, inspired by the heritage of glass ships in bottles and the skills of scientific glassblowing.

Related publication: Vessels of Memory: Glass Ships in Bottles, Ayako Tani, Art Editions North, 2018.

The Scottish Maritime Museum is based at the Linthouse Building, Harbour Road, Irvine KA12 8BT in Scotland, UK.

About the artist and curator

Ayako Tani is a Japanese glass artist and researcher based in Sunderland, UK. Her lampworked sculptures are held in permanent museum collections in the UK, Germany and China.

About the author

Emma Park is a freelance writer and Contributing Editor at Glass Quarterly.

Main feature image: Ayako Tani’s ‘City of Adelaide’ (2017) ship in a bottle. Photo: Jo Howell.