Faith in the promise of material

Netherlands-based architect and glass artist Han de Kluijver talks about his career and how he wants his glass objects to build a bridge between architecture and sculpture.

As a child, I was always impressed by mist in the countryside – the image of cows without legs. And I observed how light plays with spaces. In my final year at the Academy of Fine Arts, I realised that being an artist was not for me. I needed interaction and cooperation, and I wanted to contribute to society. In those days art training was too individualistic.

During a visit to Le Corbusier’s iconic Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut building in Ronchamp, France, I knew immediately that I wanted to become an architect. Sometimes your eyes are opened and you see things in a different light. You suddenly understand things, like you did at school. For example, once you understand the formulas in chemistry, it ‘suddenly’ becomes a fun subject.

At the kilometre-long shrine of Fushimi Inari Taisha in Japan, with its ‘tunnel’ of orange-red gates filtering the greenish light of the forest, I suddenly realised that everything is part of a larger and richer world. At such a moment, the question of what is truly important arises. What endures through time? What is essential?

After completing the Academy of Fine Arts course in the mid-1970s, I studied architecture, graduating in 1982. I also studied urban design, finishing in 1983. Then, in 1985, I founded HDK Architects bna bni bnsp.

Architecture is an ancient art: man has created floors, walls and ceilings for centuries. However, I am convinced that it is still possible and necessary to create completely new architectural forms and shapes. Ever-changing ways of life require this adaptability: our buildings and urban planning have to fit contemporary needs. Old and tested characterisations are insufficient as they primarily refer – in a nostalgic way – to a world that (possibly) no longer exists. This does not mean that we should not appreciate the old. What already exists can also be inspiring. However, for me, the search for new forms, shapes and materials is a very important aspect of architecture. A second essential aspect of the architect’s profession is contemplating space and its arrangement.

During a visit to a glass factory in Sandomierz, Poland, where I was working as an architect, I watched glass plates coming off the conveyor belt and noticed glass blowers in an adjacent workshop making Bohemian glass products. I saw the pleasure they had in working as a team. Inspired, I took a course and began experimenting with glass objects. Later, I met Neil Wilkin and collaborated with him for several years.

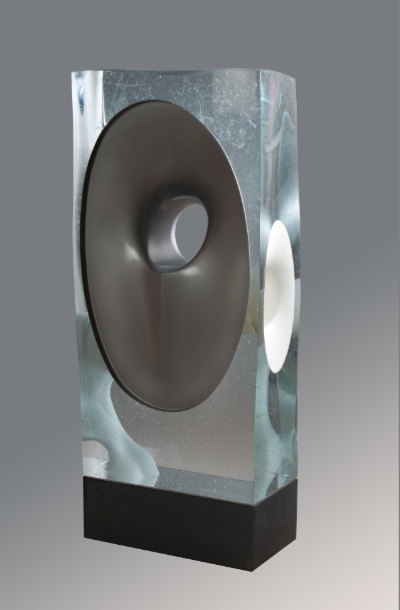

I tried blowing glass, but switched to glass melting, as my focus was mostly on forms that I could extrapolate into architecture.

Collaboration has become commonplace, with more and more talk of solidarity and community spirit. This suits me, as both architecture and glass art involve teamwork. Today, I work with craftsman Radovan Brychta, from the Czech Republic, to create my glass objects.

The demarcation of space

Art and architecture can strengthen and influence one another. Explorations into other disciplines can stimulate creativity and innovation, introduce new materials and improve technical knowledge. Nobody is just architect, artist or philosopher. Architects and visual artists are used to thinking in abstract concepts. Several realities can exist side by side. In my work, glass and architecture are always related. The two disciplines are equivalent: both come from a love of craftsmanship, in which the design process is central. In both glass and architecture, the creation has a life of its own. While working on new concepts and conceptions of glass, I research and develop a new language of form, which I may extrapolate to architecture later. By this, in a humble way, I hope to contribute to the spatial design of our living environment.

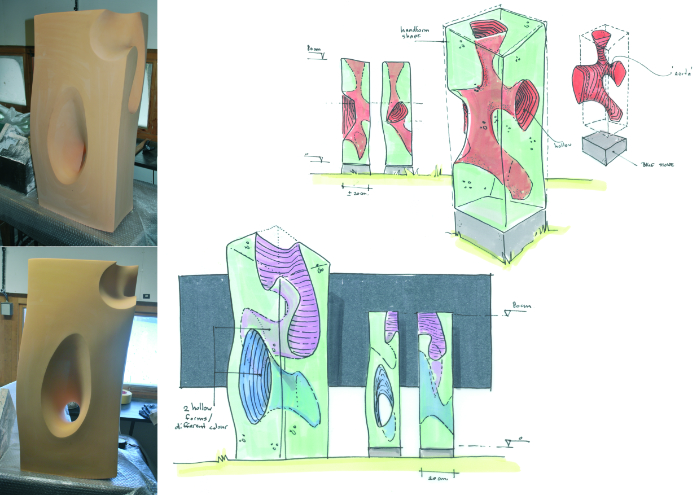

The design process is the basis for both architecture and the arts. Designing requires a specific attitude and a certain obsession. Once you have mastered that attitude, you can design either objects or buildings, or even parts of cities. For me, drawing is the necessary tool in seeking proportions, visualising space and objects, or documenting observations. As time passes, imagination and observation start to blur and drawing becomes design.

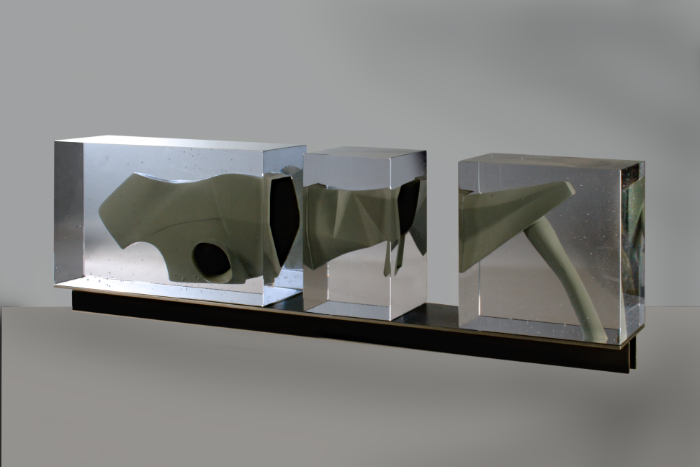

With my glass objects I aim to build a bridge between architecture and sculpture. Of course, there are boundaries between both disciplines: architecture is often more pragmatic in nature, as it is restricted by a client’s wishes and must adhere to construction building laws. And, most importantly, architecture cannot be fiction, whereas art can.

My glass objects only have a visual function, in contrast to architectural structures. But they do tell a story and are conceptual in a way no building could be. An architect creates space with the help of glass walls and facades. My glass objects only create space in a figurative sense. They are a metaphor for the literal space that architecture provides.

Architecture is about making space. The walls are not the most important thing, but the space they create is. The cast glass object is like an architectural creation: an unchanging solid form in space. The walls of my glass objects have the same function as walls in architecture.

Art – with architecture in its wake – plays a leading and vital role in the development of such structures. This is why architects and artists should always maintain a level of curiosity towards a new language of forms and the motivations that shape and re-shape our surroundings.

Find out more about Han de Kluijver via his CGS member page.

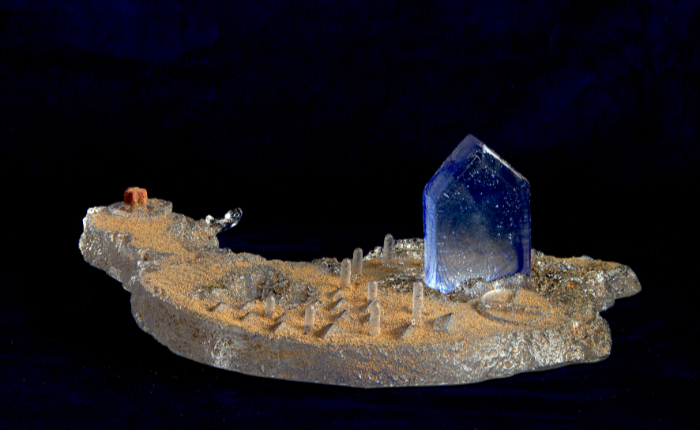

Main feature image: ‘Poetry of space’, (924 x 148 x 240 mm). Han says, “It is wonderful to be able to assign meaning, to create something more than just material and form”. Photo: Tomas Hilger.