Glorious glass textiles

Contemporary glass artist and designer Ulrike Umlauf-Orrom has taken glass fusing to a new level, inventing her own processes to create the effect of fabric, inspired by her love of Japanese art and craft. Linda Banks finds out more.

You are known for your accomplished fused glass pieces. What led you to start working with glass?

After an apprenticeship in ceramics and an industrial design degree at Munich University, I was awarded a postgraduate scholarship at the Royal College of Art in London, Faculty of Ceramics and Glass, in 1980. As a design student in ceramics, I began to cast comparative vessel variations in different ceramic materials, from clay to bone china. I was very frustrated not to be able to achieve translucent bone china vessels because of technical problems. My tutor’s comment, “Why don’t you try it in glass?” was a revelation!

I was given a warm welcome in the glass department and, in my final year, I worked in both departments. My degree show consisted of ceramic and glass objects, which was very unusual at the time.

However, I was so enthusiastic about glass as a material, with the new processing techniques I had learned, that I never worked with ceramics as a maker again – only as designer.

What glass techniques have you used, and which do you prefer?

I have never mastered glassblowing with satisfactory results, so my vessels were blown for me (in college by Fred Daden, the college master glassblower, later by Neil Wilkin in Bath). I am adept at cold working, such as grinding, polishing, engraving and various sandblasting techniques. I later learned sandcasting on a course at Pilchuck Glass School with the Swedish designer and artist Bertil Vallien, which I really liked.

Applying this technique on my return to Germany was not easy; sandcasting was largely unknown. I had to try out the glass studios I knew to find out whether sandcasting worked with their glass, equipment and annealing possibilities. This meant hiring the studios and a casting assistant for at least three days per session. I was on the road in Bavaria with my sand and the plaster models I needed for the casts, which proved expensive and time-consuming. At some point, as a mother of two young children, I decided I couldn’t, and didn’t want to, do this any more.

That was how I got into fusing. I searched for, and found, a technique that would allow me to work with maximum autonomy and exploration in my own workshop at home.

I took a fusing course at Creative Glass in Zurich and then stocked up on all the materials and tools I needed. I learned how to use a glass cutter, ordered a kiln and a grinding wheel and got started straight away.

Fusing has now been my continuous technique for over 25 years, and I am still full of enthusiasm. The most important thing for me is that I can carry out all the steps of the work myself and divide up the different phases. Working with glass panes as a starting product does not require the same continuous dedication as working with hot glass at the furnace.

What is your creative approach? Do you draw your ideas out or dive straight in with the materials?

I collect my ideas as small sketches in a detailed workshop book. I work systematically and have an extensive colour and texture pattern library with hundreds of patterns.

What is your inspiration?

Japanese arts and crafts. In my first year in London, after a visit to the exhibition ‘Japan Style’ in the Victoria & Albert Museum, I discovered and often visited its Japanese collection. I was inspired by the lacquer work, Samurai armour and, above all, the textiles. There I could find everything that still appeals to me today and reappears in my glass works: reduction, decoration with simple means such as combinations of stripes and their intersections as checks or diamonds (but no rigid geometry), sophisticated colouring, references to nature, the delicate play with structure and surface.

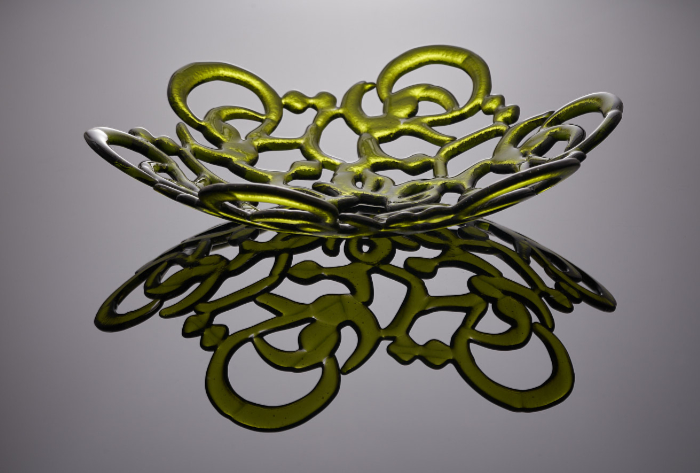

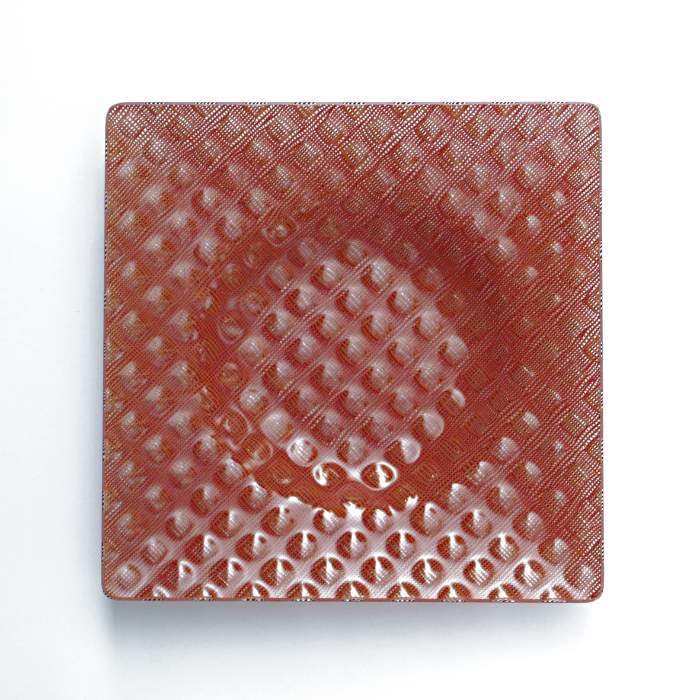

I describe the results of my fusing technique, with fine coloured lines and intersections, as ‘glass textiles’, with great similarity to the Japanese Ikat fabrics. I compose – in glass – a piece of ‘cloth’ that I place on a selected mould and then slump. The shape of the vessel is intended to show the appeal of my fabric to best advantage.

With Samurai armour, I was fascinated by the curved, lacquered bamboo plates used in combination with visible Sashiko stitches to reinforce several layers of fabric to form a padding. These structured effects have been incorporated into the air cushions of my glass pieces, where I explore how I can three-dimensionally transform the surface of my ‘glass fabrics’.

What message do you want to convey through your art?

That a bowl can be a work of art, like a painting or sculpture.

What is your favourite tool or piece of equipment and why?

My technical equipment consists of a grinding and polishing machine, a sandblasting machine and a kiln. The latter is the most important for me, as it transforms my complex three-to-four-layer constructions of glass and coloured enamel powder into a usable sandwich to work on. The kiln is also the device with the greatest transformation factor in my work. I have a lot of technical experience and, largely, the pieces can be planned. Nevertheless, opening the kiln is still a special moment. I call it the ‘miracle bag effect’. My hope and amazement at the results remain unchanged after all these years!

The ecological aspects of kiln-firing have always been important to me, so I switched to a renewable energy supplier (wind and solar electricity) 20 years ago.

Do you have a favourite piece you have made? Why is it your favourite?

One favourite piece of mine consists of two standing arch elements [see main feature image]. It is now in the National Glass Museum in Sunderland, where it was the selected fused object in the Contemporary Glass Society (CGS) exhibition, ‘It’s all in the Technique’.

It was made using my technique of enclosed air pockets, a unique crafting process I have developed. It shows the finely woven, textile-like colour lines, the transparency of the glass, plus the perfect different surfaces of the front and back.

Where do you show and sell your work?

There are fewer and fewer exclusively glass galleries, especially those that show applied glass art. My work is exhibited in glass galleries in Drachselsried and Innsbruck, as well as in galleries for applied art in Munich and Diessen. I participate regularly in national and international competitions.

Do you have a career highlight?

Six times in a row (2007-2022) my vessels were selected for the International Glass Exhibition of Kanazawa in Japan, which took place every three years. Japanese influences have had a great impact on my artistic development, and I consider it a great honour that my objects are so highly regarded in Japan in return. Unfortunately, this triennial competition has been discontinued now.

Where is your glass practice heading next?

The possibilities for new fusing variations are not exhausted yet; I am still discovering new facets. Glass casting in my kiln is another plan.

And finally…

I am delighted to have been selected for an interview for CGS Glass Network digital, as a long-standing non-British member. My introduction to glass 40 years ago was only possible in the UK and my ‘glass roots’ lie in England. I would like to plead for the exhibitions and competitions of the CGS to remain open for non-Brits in the future, as such possibilities have been painfully reduced since Brexit.

Find out more about Ulrike and her work via her website.

Main feature image: ‘Arch Segments’ (each 35 x 12 x 31cm), made in 2022, was shown in the CGS exhibition ‘It’s all in the Technique’, at the National Glass Centre, Sunderland, UK. It is now in the National Glass Centre’s collection. All images by the artist unless stated otherwise.