Interview: stained glass artist Debora Coombs

Debora Coombs is an accomplished stained glass artist with a love of geometric patterns that has led her to push the boundaries of her practice to make 3D creations based on scientific tiling. Linda Banks finds out more.

You have long experience with stained glass and an interest in geometric design. What set you on this path?

My fascination with light and geometry began as a very small child. I’d spend hours watching patterns of sparkling light cast from a streetlamp onto my bedroom window. The streetlamp always stayed at the centre of circles of straw-like scratches of light, even when I moved my head. This seemed mysterious. Now I know that light patterns, like ripples on a pond, are visual expressions of nature’s hidden energy. The sparkles I loved were caused by shifting my point of view and altering the relationship between indoor and outdoor objects and textures. Curiosity about the relationship between viewer and viewed has stayed with me, fuelling my work in glass and geometry. I use glass painting to manage the relationship between transparency and opacity and have developed techniques that allow me to do this without losing the sparkle of mouth-blown glass – a dance I find endlessly fascinating.

Geometry also has deep roots and plays a key role in my work. It started in the early 1980s when I was at the Royal College of Art working on a Master’s degree in the Ceramics and Glass department. A geometric pattern with unusual symmetry was discovered by British mathematician Roger Penrose. It grabbed my attention. I made drawings based on Penrose tiling by hand and with a plotter (a primitive type of computer printer), then painted and fired them onto glass. Then, 30 years later, I met computer scientist Duane Bailey and we built sculptural versions of Penrose tiling [see YouTube video via this link]. I learned more about the underlying mathematics, and that Penrose tiling is related to the atomic structure of quasicrystals, a type of matter that occurs naturally in meteorites. Enthusiastically I returned to the work I’d begun as a student.

What is your creative approach? Do you draw your ideas out or dive straight in with the materials?

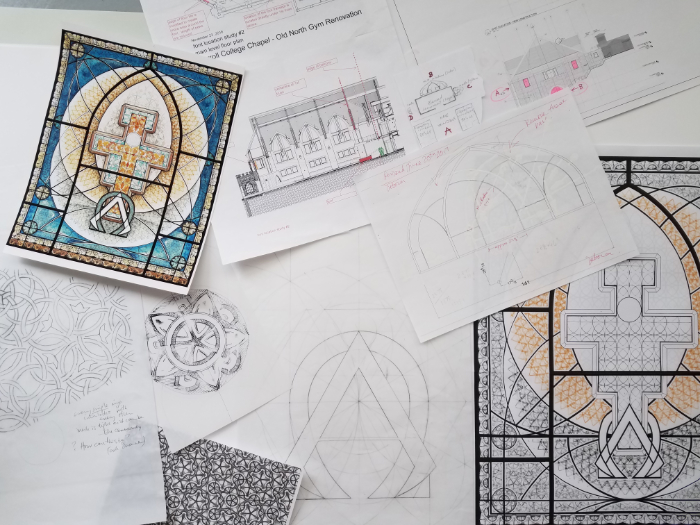

I’ve been working on the same geometric project for so long now that each day in the studio is a continuation rather than a beginning. My ‘next steps’ sometimes come in dreams, scribbled down in the morning as little diagrams and notes. Ideas also come from noticing new shapes or patterns in my existing work, sometimes almost by accident, and deciding to investigate them.

With stained glass commissions, which can feel daunting at first, I use geometry to get myself grounded, setting about with compass and straightedge to find relationships between width and height of window openings, the underlying structure of any curves or tracery, and to decide where to break the window into separate panels and place support bars. This, my first step in designing a window, is both a ritual and a practicality. It calms my mind and allows me time to consider structure before having to think about detail. It creates a solid visual and physical foundation for building a new piece of work. Ideas about colour, transparency, imagery, materials and technique flow much more easily as I begin sketching over photocopies of the geometry.

What message do you want to convey in your work?

Although my work is sometimes narrative, I’m not attached to the idea of promoting my own stories or guiding the viewer’s interpretation. When my work resonates with someone, it’s often in ways I hadn’t imagined and I really enjoy this. We are all so different, and yet we can connect, sometimes in surprising ways. The fact that we are conscious of this and can talk about it is extraordinary. This is my message, perhaps – that Nature is remarkable.

What is your favourite tool or piece of equipment and why?

I’ve begun to think of my mind as an extraordinarily high-tech piece of equipment. Used skilfully and for the right purposes, it is a remarkable tool. As I’ve grown older, I’ve learned to use my mind more creatively, not letting my brain run amok or settle into autopilot.

Besides this, my Hoaf Speedburn glass-firing kiln is my favorite piece of equipment. It is propane-fuelled, computer-controlled, anneals safely and quickly, and I love the sound of its burners clicking on and off over the gentle hissing of the pilot light.

Do you have a favourite piece you have made?

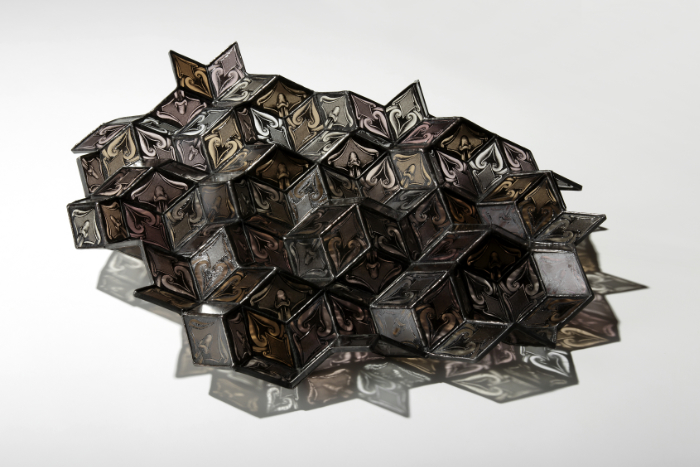

Like a child, my favourite piece is often what I’m working on when someone asks. ‘Mirrored Quasicrystal’ is a sculpture of Penrose tiling made from hundreds of identical glass diamond shapes copper-foiled, soldered together and reverse-coated with rubber to fix the mirror’s corrosion. I think of it as a hunk of meteorite, billions of years old, with fascinating geometry. As Mirrored Quasicrystal rotates [see YouTube video here], it casts shifting patterns of light in sheets that move simultaneously in different directions. Another favourite, ‘Baroque Quasicrystal’ [main feature image], is made from transparent glass painted with a coded version of the pattern’s mathematical assembly rules. It casts an image of the original, two-dimensional Penrose tiling.

Where do you show and sell your work?

I do stained glass commissions and teach twice a year at my studio in Vermont, US, and elsewhere. This allows me to continue making art that may not be of interest to anyone else. This income enables me to travel to retreats and artists’ residencies and to continue making non-commissioned work.

You are also an educator. What advice do you give to those starting out on a career in glass today?

Put a roof over your head first, pay your bills, then play freely. Indulge yourself. Make whatever interests you. Be curious. Learn new techniques. Seek out peaceful, uninterrupted time to make work, either in your studio or away from home. Show your work to others but don’t take their opinions to heart.

You have collaborated with other artists. What are the benefits and challenges of such projects?

Collaborations expand my practice in various ways, including technically, and bring new energy to my studio. Sometimes, as happened when I met Duane Bailey, they’ve shifted the direction of my work in a big way.

I began making three-dimensional stained glass with rough sculptural surfaces after building this steel and glass plank [see image below] with artist Jason Middlebrook. This post shows how we cut and welded a steel armature, wrapped it with copper foil, and used solder as a modelling material.

Another collaboration, with artist Darren Waterston for his installation ‘Filthy Lucre’, got me interested in building three-dimensional geometric work in glass and brass. Darren came with a clear vision of painting that would look old and decayed. My painting techniques are easy to master and, with a little instruction, Darren painted the glass himself. We later built another 38 lamps as a fundraiser for the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), where his work was exhibited. Since then, I’ve hosted artists working in blown glass, fused/slumped glass and ceramics and they’ve learned how to use my techniques in their own work.

A stained glass collaboration I especially enjoyed was translating a collage by Michael Oatman into this window for his space satellite in ‘All Utopias Fell’, also exhibited at MASS MoCA. Much of my enthusiasm came from not knowing how it could be done and yet somehow believing it must be possible. In the end, I got a marvellous sense of achievement from gradually figuring it out.

Do you have a career highlight?

A clear winner for ‘career highlight’ was writing and illustrating an academic paper about my geometric work. It’s very short, and probably would’ve taken a researcher just a couple of weeks, but I was starting at the bottom, learning how to describe my work accurately with words, and it took me 20 months. It describes how I discovered new fractals and methods for assembling quasicrystalline patterns in two- and three-dimensions. I was thrilled when my paper survived several rounds of peer-review and was published by Bridges Art & Mathematics in their 2021 Conference Proceedings.

Where is your practice heading next?

My long-term goal is to figure out how to build large fields of quasicrystals as simply as possible. I want to make extended sheets from individual units that snap together with magnets and connect with their neighbours in a way that continues naturally. I am currently writing another academic paper about these magnetic geometric shapes and the overall pattern of electromagnetism they create.

Alongside this, I’m working on a stained glass commission that shows the dawn sun rising over the horizon in a New England seascape. The design is partly geometric and partly naturalistic, with hand-painted native plants and flowers. The window will be traditional in many ways, but 21st century too, with images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope carved into thin layers of coloured frit in the receding night sky.

And finally…

Thank you for this opportunity to share my story with the CGS community. I’m happy to have spent my life as a maker. I love glass, paint, colour, hand tools and technology. Making art from real materials helps me see and feel Nature in a tangible way, and craftsmanship seems especially worthwhile in an age of plastics and technology. I marvel at computing and mechanisation and use them in my work. I also love making things old-style, working with my hands.

Find out more about Debora Coombs via her website: https://www.coombscriddle.com

Main feature image: ‘Baroque Quasicrystal’ (2015) comprises hand-painted antique glass, copper foil and solder. It measures 56cm x 65cm x 9cm. Photo: John Polak.