Making art on a grand scale

Amber Hiscott specialises in the creation of installations for public and private spaces around the world. She has developed her own screen-printing enamel frit technique, but her designs and choice of materials are always inspired by the location of the piece. Linda Banks finds out about the challenges involved.

What led you to start working with glass?

In the time between school and university I hitch-hiked and worked for a year around Europe, Morocco and the Middle East. A plethora of vivid visual impressions affected not just my retina, but my whole body. I spent a week in the Prado in Madrid, soaking up the light and dark of Goya; gazed, transfixed, at sun beams careening through palm leaves in North Africa, but, above all, the ravishing, Gothic stained glass in Chartres Cathedral mesmerised me with aesthetic red-light therapy.

Six months later, as a kibbutznik (after selling a pint of blood at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem), I was stunned by the Chagall windows. So, they actually had modern stained glass! It was a revelation. But it didn’t occur to me at that point that I could do it.

Back in Britain, torn between literature and art as a student at Essex University in the early 1970s, I spent most of my time role-playing in physical theatre.

My Mum became seriously ill and I was granted a year off to nurse her. As she recovered, I took my portfolio and investigated the local Art College in Swansea. The colour in my drawings interested the vice-principal. He directed me to the Architectural Glass department, where Tim Lewis offered me a place. I never looked back.

I did still manage to splice in visual improvisational performances with Ritual Theatre, after learning how to draw freely with John Epstein and Dennis Creffield (who both epitomised the Bomberg dynamism). To my astonishment, I was the only student in Wales to be chosen for the Northern Young Contemporaries exhibition, which was organised by the Arts Council.

What glass techniques have you used in your career and why do you have a preference for the methods you use today?

I don’t prefer any one technique – they all have their place in the appropriate situation.

In the 1970s, when graphic, leaded work was popular because of the German School, I was more intent on experimenting with glass applique.

My work is not technique-driven, it is idea-driven and place-centric. Often the design is prescribed by the architecture, the quality and quantity of light available – whether it is surface or transmitted – the immediate or larger environment, and the culture it inhabits.

However, screen-printed enamel frit has often been my choice of technique, because it can tick all the boxes for working on a large scale in the public realm. This is not least because it can be toughened and therefore fulfils health and safety requirements.

I’m not talking about digital printing. The screen-printing I like to use is done by hand. It is highly sophisticated and is a method that has been developed over about a quarter of a century, in close collaboration with Proto Studios.

Smaller work I like to make myself, in Swansea, or Germany, or wherever I need to go to make it.

It’s good to keep an open mind initially to see what the artwork suggests. When it’s feasible, I love to use sheets of flash glass and acid-etch it.

There is no single formula, but I can give you a specific example. I was asked to create a private domestic commission in celebration of a couple’s 50th year together. I discovered that they had met on a school trip to a waterfall in South Wales. I pricked up my ears at this information, having myself had a lifelong attraction to waterfalls. One sunny day, after much rain, in March I hiked to Ystradfellte in the Powys region of Wales, equipped with a haversack of drawing materials. Entranced by the wild energy of the place I drew from behind the waterfall. Stupidly, I accidentally dropped the sketchbook into the torrent, clambering vertiginously to save it. Drenched, but delighted, on the drive home it came to me clearly which technique I would use – water jet cutting!

I have a wide vocabulary of techniques, but contemporary experiments with staining recipes during my MA unleashed a secret painterly language, which I used in the installation ‘Tunnel of Light’ at the National Waterfront Museum in Swansea, Wales.

You specialise in large-scale public and architectural art and work internationally. How did you get into this field?

You work hard when you find what you love doing. The Architectural Glass course in Swansea equipped me well. Immediately afterwards, I had an exhibition at the Edinburgh Fringe, won various awards, and was talent-spotted by the Crafts Council. Swansea City Council kindly provided a great studio at low rent.

Subsequently, six weeks away working with Ludwig Schaffrath in Germany taught me a lot about working to scale in architecture.

Within five years I had won two major commissions in London: The Liberty Canopy in Regent Street, which we made in Swansea, and one for the Unilever Headquarters, which was fabricated by Derix Glass studio in Taunusstein, Germany.

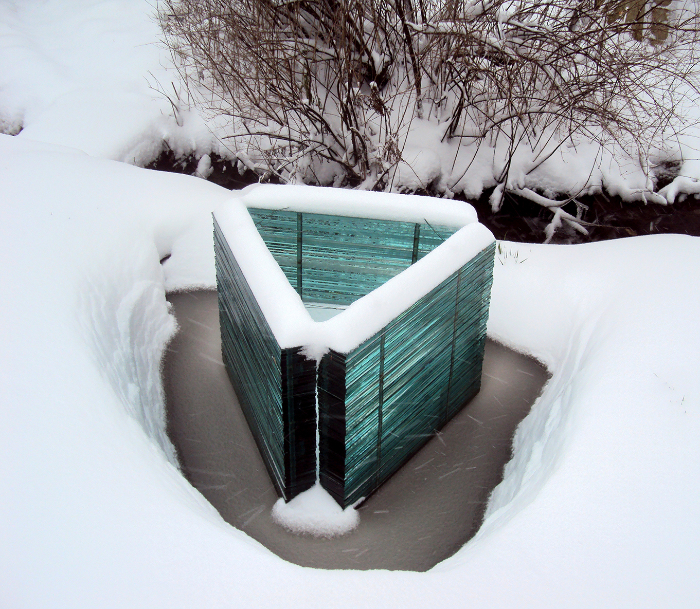

A decade later, I stepped out of the architectural framework by entering a national sculpture competition for Exchange Square, Bradford, which I won with ‘Quatrefoil for Delius’.

Are there particular design and physical challenges when working at a large scale on something that will be located in a public space? How do you translate your vision from an idea into an installed, large-scale work?

Yes of course there are huge, thrilling challenges. A scaled design is imperative. For sculptural work I make a maquette, so that it can be viewed from every angle.

However free the initial artwork may be, there comes a time when full-scale cartoons (working drawings) are required. Though now digital technology can assist in scaling up images, it is vital to make several samples – and sometimes many – to ensure you make the right decisions.

Meetings with the clients/architects/landscape designers/engineers/studio technicians/fabricators (not all at once) are vital to make sure everyone concerned is on the same page.

There’s no cost-cutting. The widgets and the neoprene all have to be specified and of the right quality.

What are the challenges and benefits of working with public bodies and boards to create glass art?

This term ‘glass art’ rankles with me. I set out to make art by finding an idea which is site-specific. If glass is the right medium for its realisation, then so be it! If not, then I am happy to use the appropriate one – anodized aluminium, felt, bone, or whatever.

There’s always an element of public bodies/boards or committees involved with artwork in the public realm. The design is for the people, and therefore needs to be chosen by a selection of their representatives. (This is my early education in revolution in Essex University speaking).

However, as an artist and an individual, I like to do extensive research and come up with my own ideas, rather than having them totally prescribed. All public art commissions are competitions. If I get through to the short list, my approach is to present what would excite me in the given space.

You win some, you lose some. I am not prepared to give away ideas; they don’t grow on trees; they grow on synapses with a healthy dose of play.

Public bodies are like individuals and vary according to their disposition. Often one or two strong personalities call the shots. You have to take that in your stride. Think of it as a performance. Be clear about your own intentions. At the least new people will get to see your work.

I was once disappointed to lose a commission for a chapel in a hospital. However, it turned out that the CEO had liked my work so much that she had something bigger in store for me instead.

What is your favourite tool or piece of equipment and why?

I don’t have one favourite tool, but I rarely travel without a whole battery of brushes for both paper and glass. I love to use tubes of watercolour with massive wall painting brushes.

At heart I am a painter.

What message(s) do you want to convey to your audience through your work?

This is a big question. There’s an hour-long Australian podcast that might explain it here: https://thresholds.podbean.com/e/thresholds-sally-neaves-interviews-amber-hiscott/

Do you have a favourite piece you have made? Why is it your favourite?

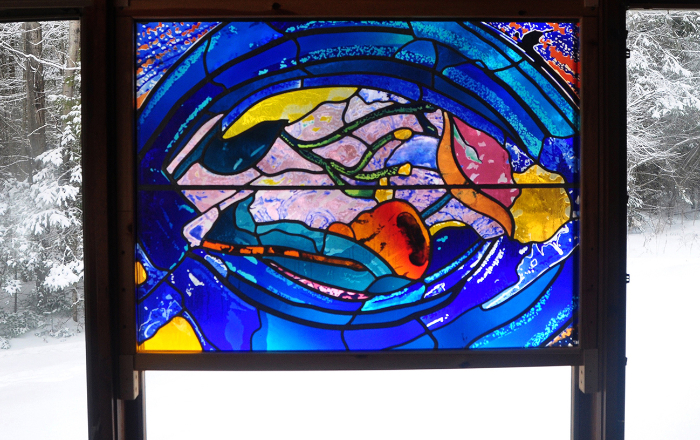

I don’t have a favourite, but there are many that come close. The community response brings me joy and fulfilment. I also like a challenge. For these reasons, the Green Mountain Monastery windows are important to me. There’s a film on Vimeo with a great soundtrack that explains more. Just google ‘Artist in nine minutes – Amber Hiscott’ to find it.

Where do you show and sell your work?

I have not had a one-woman show for years. It is time that I did.

However, I show internationally in group exhibitions most years, often with the Women’s International Glass Workshop. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, I showed twice in Japan and twice in Jaipur. These exhibitions were not always glass. Some were for mixed media and some were for paintings.

I also exhibited in ‘Concept and Context in Architectural Glass, Amber Hiscott and David Pearl’ at King’s College, Cambridge, in 2017. Before that I took part in an eclectic, John Ruskin-related exhibition in Sheffield Museum.

Climate change may be our downfall. I have been glad to show work in relevant exhibitions in recent years.

I look forward to showing at FLOW, the exhibition of contemporary glass, at Craft in the Bay in Cardiff this Spring 2022.

Who or what inspires you?

Silence. Though it is hard to find.

Energy rooted in the natural world. The prehistory and continual development of the Cosmos.

Has the coronavirus impacted your practice?

Of course. Nevertheless, I did curious paintings on paper, and weekly collaborations online, which resulted in intersectional exhibition work about climate change (not involving glass).

In conclusion

And finally, may I mention one piece of shameless advertising? I shall be teaching in Bild-Werk Frauenau in Germany in late August 2022. It would be good to have some British students.

About the artist

Amber Hiscott is a painter, sculptor and architectural glass artist living and working in Wales.

Her architectural glassworks in situ include: Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester; Sheffield Cathedral Lantern; Wales Millennium Centre; Lamberts Glass Factory, Waldsassen; Casa Foa, Buenos Aires; Green Mountain Monastery, Vermont.

Her sculptures in the public domain include: ‘Leaf Boat’, Swansea; ‘Quatrefoil for Delius’, Bradford; ‘Blue Towers’ and ‘Razor Shells’, Cardiff (in collaboration with David Pearl).

Amber’s work is in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Frauenau Glass Museum, Germany, and Nishada Museum, Toyama, Japan.

While still in her 20s, Amber received the Freedom of the Worshipful Company of Glaziers, and the Freedom of the City of London for her contribution to architectural glass.

Immediately before the first lockdown, in March 2020, Amber represented Britain in the Women’s International Painting Camp at JKK, Jaipur, India.

Find out more via her website: www.amberhiscott.com and follow her on Instagram: @amber_hiscott

You can also watch the film ‘Amber Hiscott – Red Lady Drawn into Paviland’ by David Pearl/sound Peiriant via thisYouTube link: https://youtu.be/8cqJWQRWbMM

Main image: Detail of ‘Colourfall’ at the Wales Millennium Centre. All photos used in this article are copyright of Amber Hiscott.