We are delighted to announce the results of the Contemporary Glass Society (CGS) and Glass Sellers’ Graduate Prize and those who will be featured in the New Graduate Review publication, which will be circulated to CGS members in November with the Glass Network print magazine, as well as included in the prestigious Neues Glas/New Glass Art & Architecture magazine.

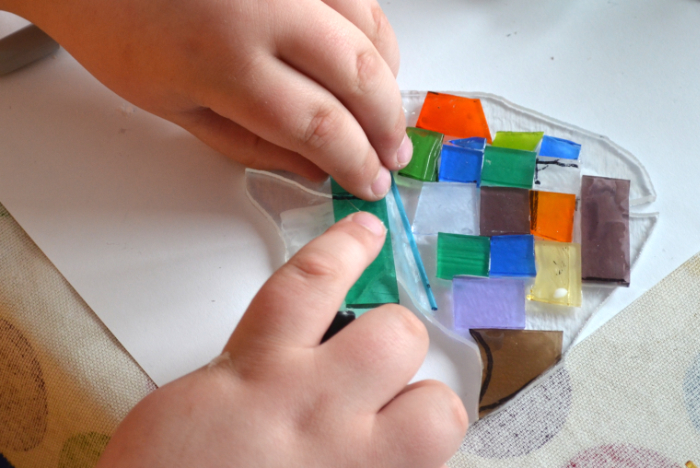

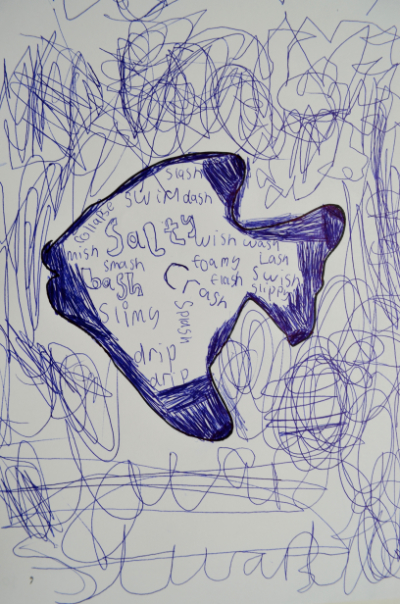

The winner is Sally Scott who graduated from De Montfort University. Sally has a background in scientific research and has taken inspiration from the processes underpinning Molecular Biology to inform her new-found glassblowing practice. She wins £500 cash, £150 vouchers from Creative Glass UK, a promotional package including the cover and feature in the New Graduate Review, two years’ CGS membership, a year’s subscription to Neues Glas – New Glass: Art & Architecture magazine, plus a selection of books from Alan J Poole.

Speaking about her success, Sally said, “I am absolutely delighted to have won this prize. Having come to glass blowing from a background in science rather than art it means a great deal to have my accomplishments recognised and celebrated. Winning this prize has given me the confidence and belief that I can continue to develop my skills and move forward to pursue a career in glass.”

In Second place is Suzie Smith from the University of Sunderland. The judges really loved her piece ‘The Alchemy of Fungi’. Suzie is deeply interested in the connections we experience, whether through the natural world, sensory elements, or personal memory. The judges said the piece really connected with them, too.

“I’m delighted to have been awarded second place in the Glass Sellers’ CGS Glass Prize,” said Suzie. “I’m excited to continue exploring the connections found in nature, especially the hidden lives and patterns that lie just beneath the surface.”

The runners up were Moonju Suh, who is completing her PhD at Edinburgh College of Art in 2025, and April HilingRoss who took her BTEC at Morley College, London.

Leigh Baildham (Chairman of Charity Fund Trustees at the Worshipful Company of Glass Sellers of London), Mike Barnes (CGS Treasurer and glass collector), Helen Slater Stokes (CGS Administrator) and Sarah Brown (CGS Chair and Project Manager) met in London to judge the prize and spent many hours choosing the winner, second place and runners up, along with awarding four entrants Highly Commended: Charlotte Wilkinson (De Montfort University), Sean Barnes (University of Sunderland), Pernille Adriana Bach (Riksglasskolan, The National School of Glass, Sweden) and Alison Stott (Arts University Plymouth).

Sarah Brown commented, “I’d like to thank all of the students who applied, and wish them every success in the future. This year we opened the opportunity to Europe and received applications from a wide range of universities and colleges, as well as a wide range of course levels, from BTEC through to PhD. Whatever stage you are at on your glass journey, we want to celebrate your success and support the future of glassmaking far and wide. We hope to build upon this next year, getting even more applications from the UK and across Europe so we can support even more graduates.”

All those selected to feature in this year’s New Graduate Review are:

Winner: Sally Scott, BA (Hons) Design Crafts, De Montfort University

Second Prize: Suzie Smith, BA (Hons) Artist Designer Maker: Glass and Ceramics, University of Sunderland

Runner Up: Moonju Suh, Design PhD, Edinburgh College of Art

Runner Up: April HillingRoss, BTEC National Certificate in Art and Design (Glass) Level 3, Morley College London.

Highly Commended:

Charlotte Wilkinson, PhD, De Montfort University

Sean Barnes, BA (Hons) Artist Designer Maker: Glass and Ceramics University of Sunderland

Pernille Adriana Bach, Nordic Programme in Glass Craft and Cold Working Techniques & Design and Art Glass Program, Riksglasskolan, The National School of Glass, Sweden

Alison Stott, MA Glass, Arts University Plymouth.

Also selected to be included in the magazine are:

Aisha Airan, University for the Creative Arts

Calum Dawes, Royal College of Art

Emma Marie Martin, University of Wales Trinity Saint David

Hannah Masi, University of Sunderland

Helen Gordon, University of Sunderland

Irina Levina, Stroganov Russian State University of Design and Applied Arts.

Jiawen Xu, Morley College, London

Kerry Roffe, University of Sunderland

Miyuki Guo, Royal College of Art

Natasha Redina, Royal College of Art

Marie Joy Risser University of Wales Trinity Saint David.

CGS is grateful to the Worshipful Company of Glass Sellers of London Charity Fund, Professor Michael Barnes MC FRCP and our esteemed sponsors, Creative Glass, Pearsons Glass, Warm Glass, Neues Glas – New Glass: Art & Architecture and Alan J Poole, who enable us to offer this award for graduates each year.

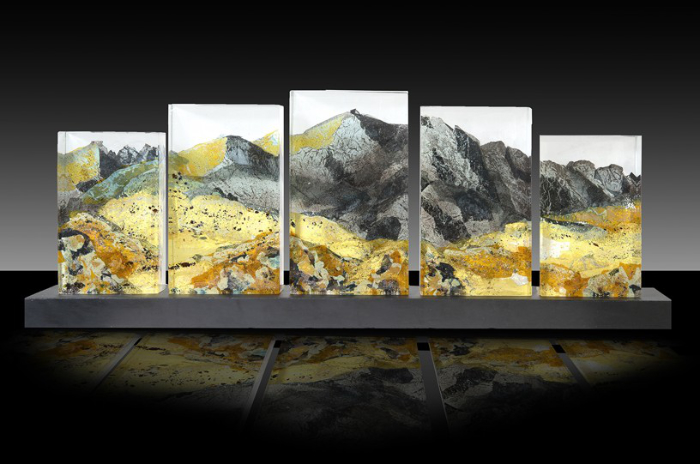

Image: ‘Morphology Collection’ by winner Sally Scott. Photo: Simon Bruntnell.

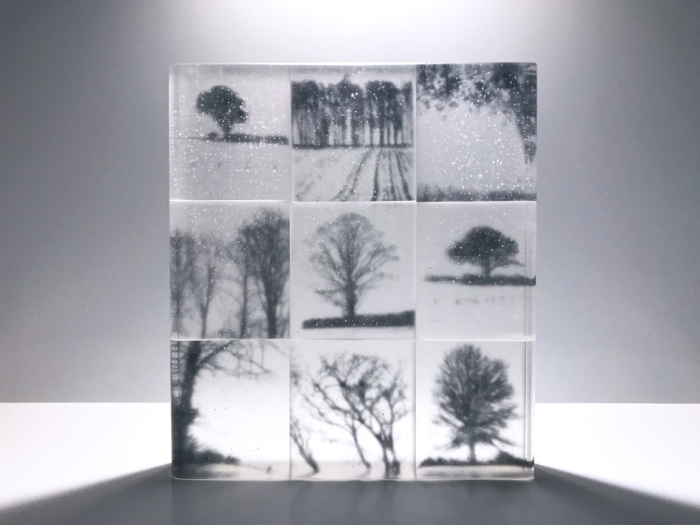

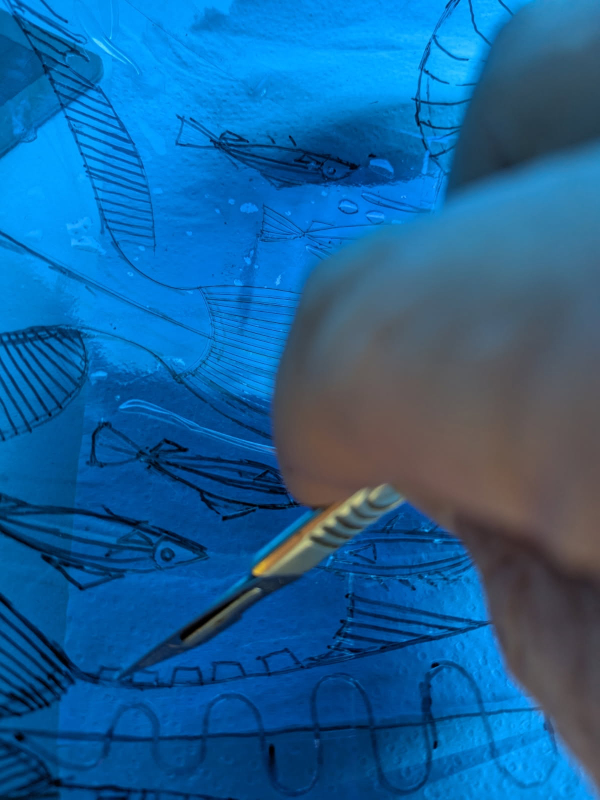

I began experimenting with Graal – something I still do. It gives the glass the opportunity to ‘speak again’ by softening and distorting my crisp images into more fluid and gentle shapes.

I began experimenting with Graal – something I still do. It gives the glass the opportunity to ‘speak again’ by softening and distorting my crisp images into more fluid and gentle shapes.

I enjoy teaching at home, at the Glass Hub, or at Bild-Werk Frauenau Summer School in Germany. Sandblasting is quite a simple technique to grasp so I like to help my students to fine-tune their design elements and to work in a methodical way. My visual reference is renewed by the different ways of seeing that my students bring to the courses, be they plumbers or PhD students.

I enjoy teaching at home, at the Glass Hub, or at Bild-Werk Frauenau Summer School in Germany. Sandblasting is quite a simple technique to grasp so I like to help my students to fine-tune their design elements and to work in a methodical way. My visual reference is renewed by the different ways of seeing that my students bring to the courses, be they plumbers or PhD students.

In conclusion, I’d like to mention the tutors’ ‘visitors book’ at Bild-Werk Frauenau, which is a reflection of the open-minded and sometimes chaotic intensity of the Summer School. No creative tutor is going to just write their name, which makes this book a kaleidoscope of uninhibited, arty joy. As someone who also trains horses, for my contribution I drew two horses, representing hot and cold glass, ‘cantering upsides’, with me balancing a foot on each. Often, in the glass world, these horses move apart from each other, but, under my weight, they can come together, willingly and naturally, to great effect.

In conclusion, I’d like to mention the tutors’ ‘visitors book’ at Bild-Werk Frauenau, which is a reflection of the open-minded and sometimes chaotic intensity of the Summer School. No creative tutor is going to just write their name, which makes this book a kaleidoscope of uninhibited, arty joy. As someone who also trains horses, for my contribution I drew two horses, representing hot and cold glass, ‘cantering upsides’, with me balancing a foot on each. Often, in the glass world, these horses move apart from each other, but, under my weight, they can come together, willingly and naturally, to great effect.