Simon Moore: A personal view of glass education

There is no doubt that Simon Moore is driven in everything he does. Having built his first wood-fired pottery kiln at age 14 to running a thriving glass studio today, his unerring commitment to creating production glass for businesses is the foundation of his success. However, he worries that students today are not able to benefit from the sort of educational and training mix that was the basis of his career. Linda Banks finds out more.

Simon Moore describes himself as a “production handmade glassmaker”. He is proud of this title, which he believes encompasses his hard-won skills of repetitive making, building accuracy and speed, which have enabled him to found and maintain a sound and profitable business. His aim is never to have products sitting on his shelf unsold.

Though Simon went to art school, he deliberately does not call himself an artist, as he does not believe this term justifies his broader abilities. In fact, he took a year out of formal education to train at the Glasshouse in Long Acre, Covent Garden, in 1979.

As experienced glassblowers know, it takes time to learn the basics and the ‘haptic’ knowledge necessary to be proficient in glassmaking. He recognised that hard work would be needed if he wanted to make a successful career with glass. He comments, “I had just enough skill, but, importantly, the right aptitude to gain more. I often worked 14 hours a day and was paid £45 per week.”

Simon knew that he had to be totally committed to learn this trade through working long days, learning how to fill the furnace and seeing how a workshop runs. He also benefitted from training in the exacting skills of making the same piece over and over again, watching the talented glassblowers there, especially gaffer Ronnie Wilkinson, of Whitefriars fame.

When he was a student at the then West Surrey College of Art and Design (now UCA Farnham), Simon acknowledges that he was fortunate to be immersed in an atmosphere of keenness to make, surrounded by workshops for ceramics, metalwork and jewellery for inspiration and with the support of tutors like Annette Meech, Ray Flavell and Stephen Procter.

However, he believes that colleges today are not investing in the teaching of glassmaking so that students can leave with enough ability to work in the real world. He says, “The colleges are teaching what they perceive as art because they describe themselves as art schools. They are not looking for students with aptitude. Nor are they looking for students with talent and ambition, either. For them I think it’s all about getting ‘bums on seats’. The job of an educator is to extend the student, to understand ambition and help the student achieve it, but I don’t feel this is happening now.

“I myself taught at art school for many years and loved it. But I became increasingly aware that courses were teaching not how to make an idea happen, but how to think about how it happens. If you have a good idea and can’t make it yourself then you use glass makers like James Maskrey or Louis Thompson. But as we all get older, where will the next generation of glass masters come from?

“What makes me anxious today is the lack of decent glassmaking assistants. They are just not out there any more. Glass making needs a physical, hands-on approach. Yes, every object needs a good idea driving it and of course the intellectual side is important, but there also has to be a physical, hands-on approach. I’d much rather be able to manufacture that idea and create income than just write about it. The academic approach over the last few years is stifling physical making.

“I became disillusioned with teaching when I was told that we could not fail anyone; that was the end for me. My 37 years of experience in the field and ability to recognise real aptitude for a career in glassmaking – or lack of it – apparently counted for nothing. The world of academia is so different to the world of professional and commercial practice.”

Following on from his intensive work experience and subsequent employment at the Glasshouse, Simon proceeded to co-found the Glassworks studio with Steven Newell and Catherine Hough, in order to produce innovative glassware.

For him, it has always been about the ability to make the same item to the same high standard and precision, over and over again, that has appealed, and he is proud that he can make the same decanter for a client today that he made five years ago.

Over the course of his career Simon has travelled and worked abroad extensively, feeding his knowledge and building influential contacts. “To be a good glassmaker, you have to keep learning all the time,” he emphasises.

However, he does not see the drive necessary for success in many students graduating today. “They don’t have the patience or the 100% commitment required. They really have to want to do it and understand the level of dedication it takes to learn. You can lead a horse to water but can you make it drink? In their turn, the students must keep the pressure on the colleges to give them access and practise their skills with commitment – a couple of hours a week is not enough!

“The colleges need to be more rigorous in choosing students with the right attitude and aptitude – and then give them enough access to the hot shop to practice and fail and learn from their mistakes. There needs to be much more careers advice and discussion of business methods, preparing students for the real world. It is up to the students to demand a return on their £9,000-a-year investment if they don’t feel they are getting value for money from their courses.”

Simon’s own determination to be successful in the glass world led him to take on design directorships at Salviati in Murano and Dartington Crystal in Devon, before setting up his own workshop in London. His studio has made chandelier arms for the Palace of Versailles and glasses for Bombay Sapphire, plus he has collaborated with Anish Kapoor and Nicole Farhi to make handcrafted collections.

So, does he think the contemporary glass scene is still viable? Simon says he still has hope: “I think we still have just enough resources to rekindle some parts of a derelict tradition. We live in cycles; we reinvent. It’s time for the teaching of craft to be reinvented. Let’s get back to making. We need one very good handmade glass course that sets the standard.”

He concludes, “I just want students today to have the opportunities that I did.”

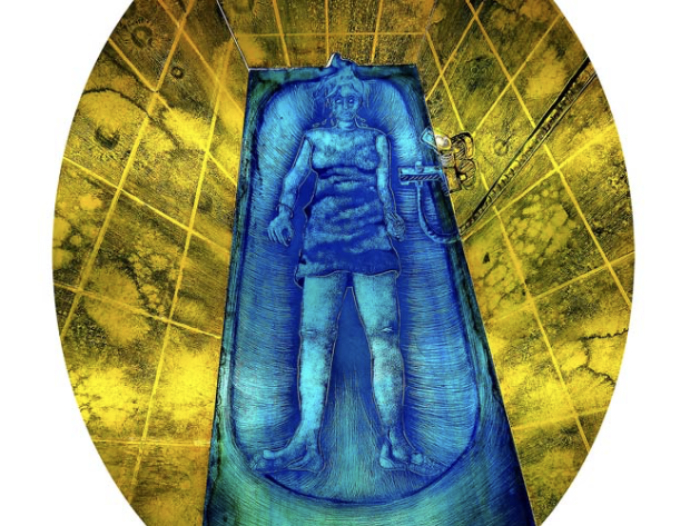

Main image: Simon Moore making a large ‘Grid Vase’ at the Kings Cross workshop.

Simon has opened the debate on glass education and welcomes your thoughts, whether you are an educator, student or someone who appreciates contemporary glass. Email us with your views via: editor@cgs.org.uk