The evolution of 3D printed glass

Today, it is possible to 3D print everything from body parts to houses. But 3D printing of glass faces challenges, not least because of the high temperatures required to keep it fluid while the shape is extruded. Glass Network digital’s editor, Linda Banks, examines the progress that has been made in glass 3D printing in recent years.

In 2015 an Israeli startup, Micron3DP, was one of the first to successfully 3D print with glass in a hot liquid form. The company stated that it had managed to “print ‘soft’ glass at a temperature of 850 degrees, as well as borosilicate glass at a melting temperature of 1640 degrees Celsius”. It used “an extremely hot extruder” for the task.

Micron3DP was able to create accurate and unusual shapes with its extrusion process, which even led to a collaboration with Swarovski to 3D print its crystal glass. Swarovski were sponsors of the 2017 Designers of the Future awards and one of the winners, TAKT Project, used Micron3DP’s printing process to create a Printed Crystal series of candleholders and vases. The pieces, which were inspired by frost crystals, had fine, gently ribbed textures and a thickness of just 1.5mm. They were shown at the Design Miami/Basel exhibition 2017. See images of the vases in this article by Dezeen.

However, by 2018, Micron3DP had decided to shift its focus away from 3D printing of glass. In an interview with 3D Printing Media Network, the company’s CTO Eran Galor noted that the main challenge was to educate the market. He likened the problem to that faced by the development of fibreoptics in the 1980s, when “nobody knew what it would be useful for because the internet had not been invented yet”. In the case of 3D glass printing, he said, “We cannot clearly pinpoint the market yet, but it could become a huge opportunity.” He explained that engineers needed to understand how to design for 3D printing, which offered the opportunity to create a huge variety of unique shapes. He cited the company’s work with the University of Helsinki in Finland, during which they collaborated on the design of a complex microfluidic tool that they were able to print in less than 10 minutes.

While Micron3DP clearly believes there is potential for its glass printing technology, particularly for applications in the pharmaceutical industry, its commercialisation has been shelved for the time being.

Meanwhile, academia was also developing its own 3D print solution for glass. Teams from the US-based Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Mediated Matter group, Department of Mechanical Engineering and Glass Lab showed off G3DP, their own additive manufacturing process for 3D printing optically transparent glass, in 2017.

This featured a high-heat extrusion printer, fitted with two heated chambers. One contained the molten glass, and a ceramic print nozzle extruded the molten soda-lime glass into the second, annealing, chamber at a temperature of around 1000 degrees C. The second chamber was maintained at around 500 degrees C, just above the annealing temperature of the glass, until the printing of the design was complete. Then the chamber was cooled gradually.

The MIT team has since continued to refine its technology, with its G3DP2 platform combining a digitally integrated three-zone thermal control system with four-axis motion control.

In order to test its capabilities, a set of 3m-tall glass columns was created and shown at Milan Design Week in 2017. In the abstract for the article, ‘Additive Manufacturing of Transparent Glass Structures’, the authors stated that the project highlighted “the geometric complexity, accuracy, strength and transparency of 3D-printed glass at an architectural scale for the first time, and a critical step in utilizing the true structural capacity of the material”. Watch the printer in action and the creation of the beautiful glass towers in the video GLASS II via this link .

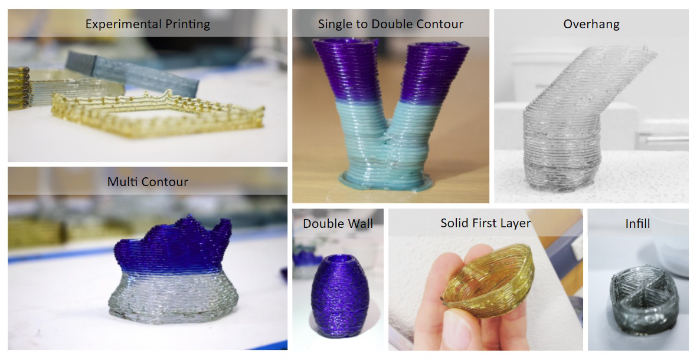

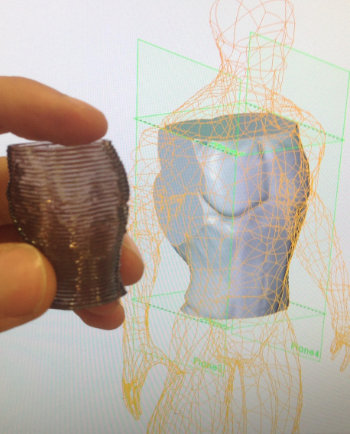

On a smaller scale, Australia-based Maple Glass Printing has been experimenting in the 3D glass printing field since 2017. The company’s CEO, Darren Feenstra, and CTO, Nick Birbilis, believed there was a gap in the market for a more affordable glass printer that would have a wide range of commercial applications. They decided to retrofit a polymer 3D printer to see if it could do the job.

It took two years of work and experimentation to create the preliminary prototype. They applied for a patent and received grant funding to commercialise their 3D printer towards the end of 2020.

According to Tony Koutsonikolas, Maple Glass’ Head of R&D, two important benefits of this printer are that it is able to use 100% recycled glass and that its processes are less energy intensive. The glass is only heated for a few minutes at high temperature to soften it. This means that the printer could help in the push to create a more sustainable society, as the company’s central mission is to reduce glass waste by 3D printing it for a second life. He points out that Australia alone uses 1.3 million tonnes of glass each year.

The team has focused on experimenting with recycled bottle glass, as one of the goals is to reduce the amount of such glass being sent to landfill. The problem has been that different types of glass melt at different temperatures, which means all the types have to be sorted, and they are difficult to reuse. Existing recycling processes currently require clean glass to be mixed with the bottle glass and energy usage is high. Maple Glass see their printer as a possible solution – a tool to process this ‘waste’ mixed glass, make new products and reduce the burden on the environment.

Currently the extruded glass layer height used by the printer is 1mm, but the plan is to reduce this in due course. This would enable the production of pieces with flatter surfaces. They could also be further smoothed, polished or drilled with a diamond-tipped tool once cooled.

Objects created so far have been a maximum of 150mm in height, but the hope is that the commercial version could create items even larger and in a range of colours.

As with other 3D printing technologies, printing time varies significantly depending on the size, shape and complexity of the item. A small perfume bottle, for example, may take one and a half hours to print, Tony explains.

He suggests another application for the 3D printer is as an enabling technology, offering a way for artists to create designs digitally and iterate versions easily. The company is open to discussions about innovative ways in which the printer could be used, so if you have an idea, look at their website and get in touch.

Tony is pleased to announce that the commercial version of their 3D printer for glass will be launched this month (January 2021) and you can read more about its technical specifications and possible applications here.

Perhaps the world is now ready to embrace the potential of 3D glass printing.

Main feature image: Glass 3D printing capabilities. Photos: Tony Koutsonikolas.