Where to start with waterjet technology in contemporary glass design

Vanessa Cutler has been working with waterjet technology in her glass design since the 1990s, prompted by a pre-internet search for an engineering company willing to cut some glass. Since then, she has consulted with businesses, artists and students to help them use waterjet technology successfully. Here, she explains what it is and how glass artists can harness its capabilities to get the best results.

Waterjet technology offers endless possibilities to artists, not only from an artistic, but also from an economic, standpoint. It enables the cutting of complex forms, cuts thicknesses from 1mm to 300mm and can be quicker and more efficient than having someone cut the material by hand. It also minimises waste and many larger studios and individuals use it for this reason.

The cost of cutting may seem high, but, for multiples, exactness of form and cutting thicker glass, it is a good process and cost effective.

So what is waterjet technology?

Waterjet technology uses water under high pressure (around 50-60,000psi), which is pushed through a focusing tube and mixed with an abrasive (usually garnet) to create a jet. This jet is powerful enough to cut materials such as glass, steel and stone. Pure waterjet, that uses water alone, is used to cut softer items, such as paper or food. The jet washers used to clean pavements and cars are a basic example of how waterjet technology operates.

Designing for waterjet technology – where do you start?

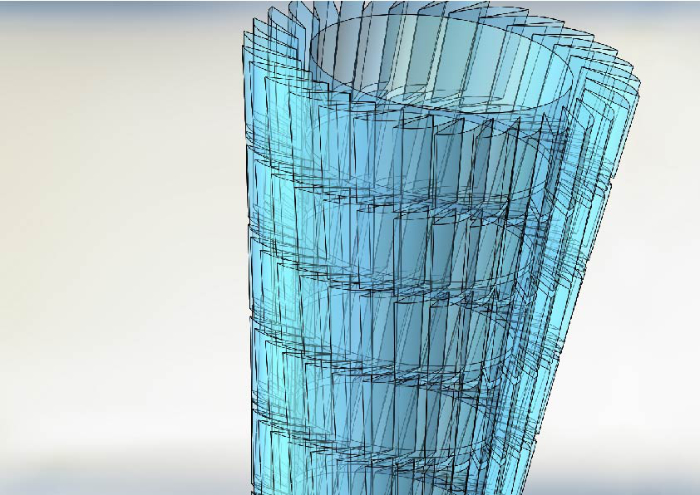

Before you use waterjet technology to create your glass art, you need to produce your design in a format compatible with the waterjet machine. For this you will need to produce a Computer-Aided Design (CAD) file. These can be made in graphic design software, such as Adobe Illustrator (Creative suite), Rhino, or AutoCAD.

Draw an outline of the shape required and ‘save’ or ‘export’, depending on the software used, as a DXF (Drawing Exchange Format) file. A DXF file is a universal format for storing CAD models. A vector file is used for flatter cuts in 2D. It changes your drawing into a series of lines/code that the waterjet machine can read to plot the cutting route.

It is important that your drawing has a simple outline. A frequent mistake artists make is providing files that are filled in inside the drawing outline. This means that the programmer will either be unable to read the files, or they may be too messy to use. The cleaner the drawing, the less time the programmer needs to work on it.

If you need multiples cut, just give the programmer one drawing and the quantity required. They will ‘nest’ the drawing to fit onto the sheet of glass that you, or they, supply. Nesting is where many different parts are fitted into a sheet in an optimal configuration to avoid wastage.

If you need a piece of glass with a shape cut out, provide enough glass to cut the internal shape out with a margin. You only need to allow about 10mm extra in this case, but it makes set-up and programming much easier. It takes more time to line up and centre a single piece of glass.

What sorts of glass can you use with waterjet technology? You can use any glass, from 3mm stained glass sheets up to 20mm float glass – and even thicker.

Although I have used these machines for many years, I still find new approaches to working with them. The different ways people work the material offers something new to learn, whether for set-up, holding delicate pieces in place, or removing glass after cutting. Like any process, the more time you spend using the technology, the more you adapt and understand the best ways of using it.

During my practical PhD at Sunderland University, I saw the first waterjet machine set up in a glass environment. I had three days’ training and was then handed the keys. That’s where my training started. I learnt by cutting glass – and a variety of different materials – for others. This approach continued when I moved to Swansea, where I cut, and helped others apply the technology.

For the past five years I have not had immediate access to a machine and now work directly with industry. Once every 4-6 weeks I travel 4-5 hours to a company to cut work. All the computer file work is done prior to my visit. Where possible, I try to get the glass there ahead of time, as sometimes they can fit creation of small files around other commitments.

Allow time

It is important to understand that the work may not be cut on the day you send a file. Programming, setting up and the time needed for cutting work vary, depending on the thickness and complexity of the form. You may be expected to leave the glass and wait for them to contact you when it is done. Turnaround time can be from 7-21 days.

The waterjet firm may look at the file programme, give you a cost and await your approval before cutting, then invoice afterwards.

Some waterjet companies you approach may not have worked with glass before. This was the case with a company I encountered when on a Wheaton Arts residency in the USA. However, that local company was willing to give it a try. I left the glass with them and collected it later in the week. Over those few days, they had played with some material and even cut their own logo for themselves. Since then, other glass artists have used their services. Therefore, if you try companies out, whether on residency or at home, you may find you are helping not only yourself but the company, too.

Providing clean, clear files and drawings is always important. The software I use is SolidWorks. This is very engineer-orientated, expensive, and not necessarily for an arts mindset. I use it for my other role delivering product design engineering at Chichester University. However, there are software options that are cheaper and, in some cases, free, especially if you only want to make the occasional file.

Other artists I know use Rhino, Fusion 360, or Adobe Creative Suite (with Illustrator generating the DXF or, with AutoCAD, DWG files). Note that when generating your file, in some software you don’t ‘save’ the file as a vector file, but ‘export’ it.

When choosing which software to use, there is no easy option. Any software takes time to learn and you’ll find ways of working and shortcuts that suit you. Nobody ever uses everything their software can do.

When designing for general cutting of flat, slightly uneven, or fused glass, keep it clean, with few segments. The form needs to be closed, with no extra lines or overlaps. Tiny curves and angles can be lost in cutting, so make the shape really defined. Glass thickness is not an issue, but it will take longer and use more garnet.

A poorly prepared file could cost you more, as the company must clean and tidy it before they can nest into the machine. The cost of software such as Adobe Creative Suite can be around £15 a month, while the cost of accessing a machine can be anything from £60-£150 an hour. Therefore, it is always best to send a file and get a cost for what you want done.

Maximise your use of the glass sheet. You can place shapes 1mm-5mm away from one another without it fracturing (depending on how well annealed your glass is). Also remember that there is a programme and set-up cost, whether you cut one piece or multiples.

Cutting axes

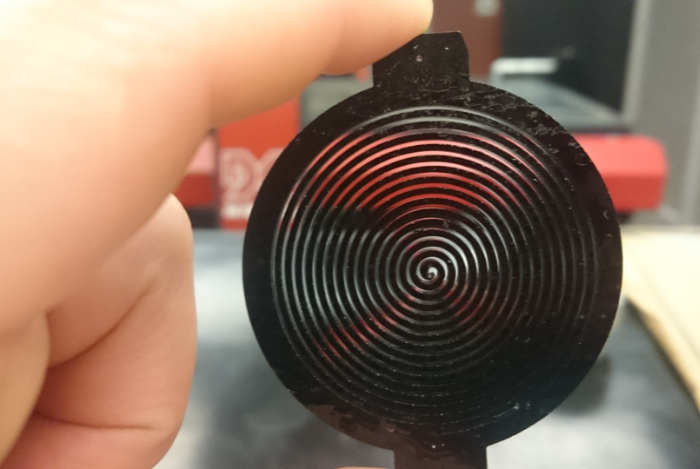

The software enables the generation of forms for both 3- and 5-axis cutting. The 3-axis is used for cutting out a flat shape via X (left/right) and Y (back/forth) coordinates, with the Z (up/down) axis generally at a fixed height about 2-3mm from the highest point of the glass, to stop any collision with the material and to maintain a continuous cutting line. Generally, the height of the head does not move to fit the contours of the material. The quality of cut can be affected by the distance of the head of the jet from the material. The closer it is to the material, the more focused the jet, while further away gives a wider, less focused cut.

The 5-axis is used for more 3D work. It allows more movement, with an A axis (angle from perpendicular) and C axis (rotation around the Z axis). However, it must keep at a set distance to stop collisions and to enable more angular cuts. It does not partially cut a surface, like a router. There are ways of doing surface abrasion, but not on large areas. Sandblasting is quicker and more efficient.

The design file you provide gives the company the visuals to programme and visually assess the viability/difficulty of your project.

Should you buy waterjet software?

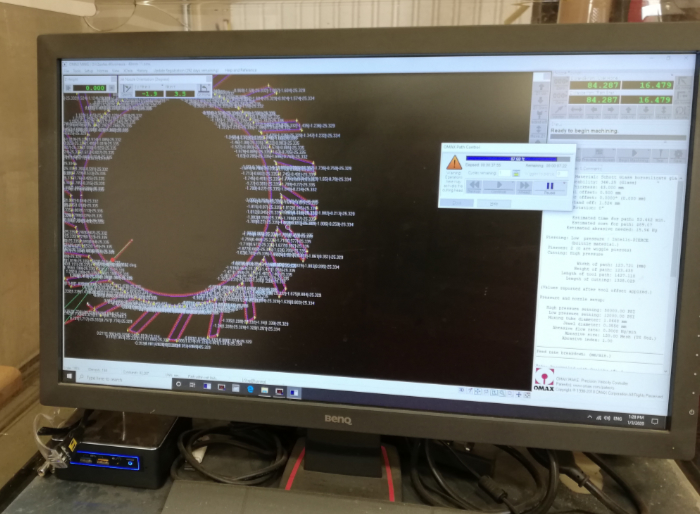

There is no need to purchase the waterjet software the machines use unless you have a machine, or are using a particular machine regularly. Plus, the machines are all different and run with different software.

For the past five years I have worked closely with Omax Corporation. I have spent time at their HQ using their Intelli-MAX software to scan the handwriting used in my recent work.

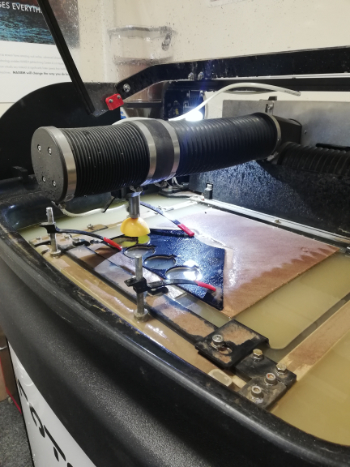

At the 2021 Glass Art Society (GAS) conference I demonstrated the production of a piece of glass on Omax’s compact ProtoMAX waterjet machine, from file, through set-up and cutting. (Contact me if you would like to see it). Whether cutting small or large, the same principles apply; you require the same DXF files to generate your shapes.

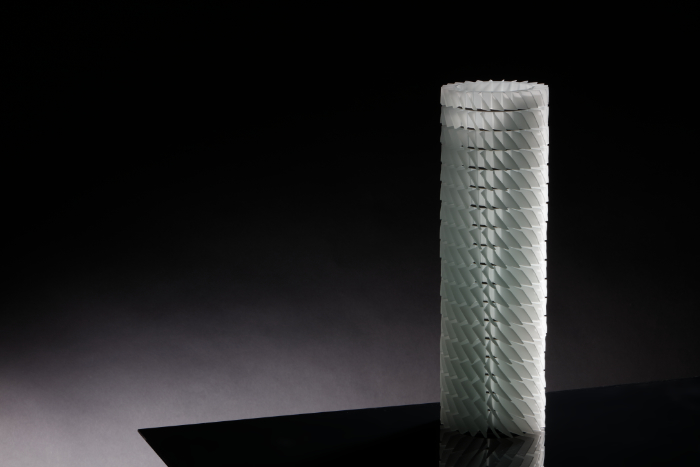

However, in the case of artworks such as ‘Flight’ (main image above) and ‘Mechanics’, the cutting was overseen by an operator following my specifications, as they were created using 5-axis technology.

Not every waterjet company can do 5-axis cutting. The majority normally cut steel and work with only 3-axis technology. They are used to cutting big, large multiple shapes that aren’t fragile and don’t need special handling like glass. They often cut using 6-80 grade garnet that can be very coarse if the feed rate and speed of cutting isn’t programmed to suit the material.

Ideally, glass needs to be cut more slowly, with a sacrificial material underneath it, such as plywood. It is worth noting that some types of plywood generate foam, resulting in a large bubble bath, which is not great when cutting delicate forms.

In my work I vary the thickness of the plywood and the material, depending on what is being cut. Many firms cut under water to reduce the noise levels. However, I prefer not to do this with glass, as smaller, break-out shapes can move and collide with the cutting head, causing blockages, dragging or machine stoppage. Where possible, weigh the glass down. It is best to weight around the material, not on it, because, as you cut, you add further tension to one area, and it may fracture.

For many, accessing a machine may be difficult. However, several organisations provide a waterjet cutting service and offer advice and help, including the National Glass Centre at the University of Sunderland, Plymouth College of Art and the University of Wales Trinity Saint David (UWTSD). In addition, Barclays Community Labs, makers’ guilds, and Fab Labs offer advice and help small businesses, sole traders, or anyone interested, to access the technology or to learn about making the files.

My best advice is to give it a go!

About the author

Vanessa Cutler is a Professor at Chichester University, an artist and a waterjet consultant. She is currently working on new work for a solo show, which will be the inaugural exhibition for the new Stourbridge Glass Museum, opening in April 2022. Her book, ‘New technologies in Glass’, published by Bloomsbury, is available on Amazon. Find out more about Vanessa and her work via her website: https://www.vanessacutler.com

Main feature image: ‘Flight’ (Dimensions 420 x 150 x 150mm), by Vanessa Cutler, shows the intricate features possible with glass that has been cut using waterjet technology. It was selected for the Toyama Glass Exhibition 2021. Photo: Simon Bruntnell.