MusVerre

Cabinets of curiosities

MusVerre

February – August 2022

“The cabinet of curiosities is a microcosm… […] a compendium of the whole nature”

Antoine Schnapper (1933-2004)

The cabinet of curiosities, a history compendium

In the 16th century, the Cabinet de curiositez or de singularitez was a source of erudition which enabled to understand the organization of the world and nature, but it was also an area of prestige in which the most precious treasures of the collector were exhibited. At that time, imagination was fertile and the cabinets were full of both ethnical and natural objects but also full of monsturositez. Traditionally, objects were sorted according to their class: naturalia (minerals, animals, plants), artificialia (archaeology, currency, weapons…), scientifica (scientific study instruments), exotica (plants, exotic animals, ethnographic objects)

Cabinets from the 17th and 18th centuries were home to an abundance of ethnological objects, coming from even more far-off journeys. Additionally, some cabinets from authentic naturalists were the subject of a classification and a printed inventory: they would later pave the way to the future Natural History museums. High schools, hospitals, abbeys and veterinary schools also had cabinets of curiosities which thus surpassed the strict and private setting.

In the 19th century, the boom in scientific research enabled the classification of species, the implementation of geological or archaeological research… Academic societies worked on the conservation and classification of the cabinets of curiosities artefacts. New museum institutions appeared and were home to many ethnological pieces.

Nowadays, cabinets of curiosities still intrigue people and a lot of museums try to present them “in their original state”.

The cabinet of curiosities at the prism of the contemporary world

Up until the end of the 20th century, only a few antique dealers or curious people were interested by the cabinet of curiosities phenomenon. It gradually took more and more space into contemporary reflections. Many scientific papers on the subject were released and museums tackled this question (Museum of Hunting and Nature, Oiron Castle…)

The cabinet of curiosities paradox lies in the desire to classify and organize everything in a scientific way, while giving space to fascination and wonder. The evocation and imaginary power of this cabinet of curiosities inspires artists, and especially surrealists or Picasso.

In the 21st century, while the extent of knowledge is vaster than ever and divided into many specialties, it would be pointless to claim seeing or knowing everything. The cabinet of curiosities can give this fleeting feeling of understanding the whole world in just the blink of an eye.

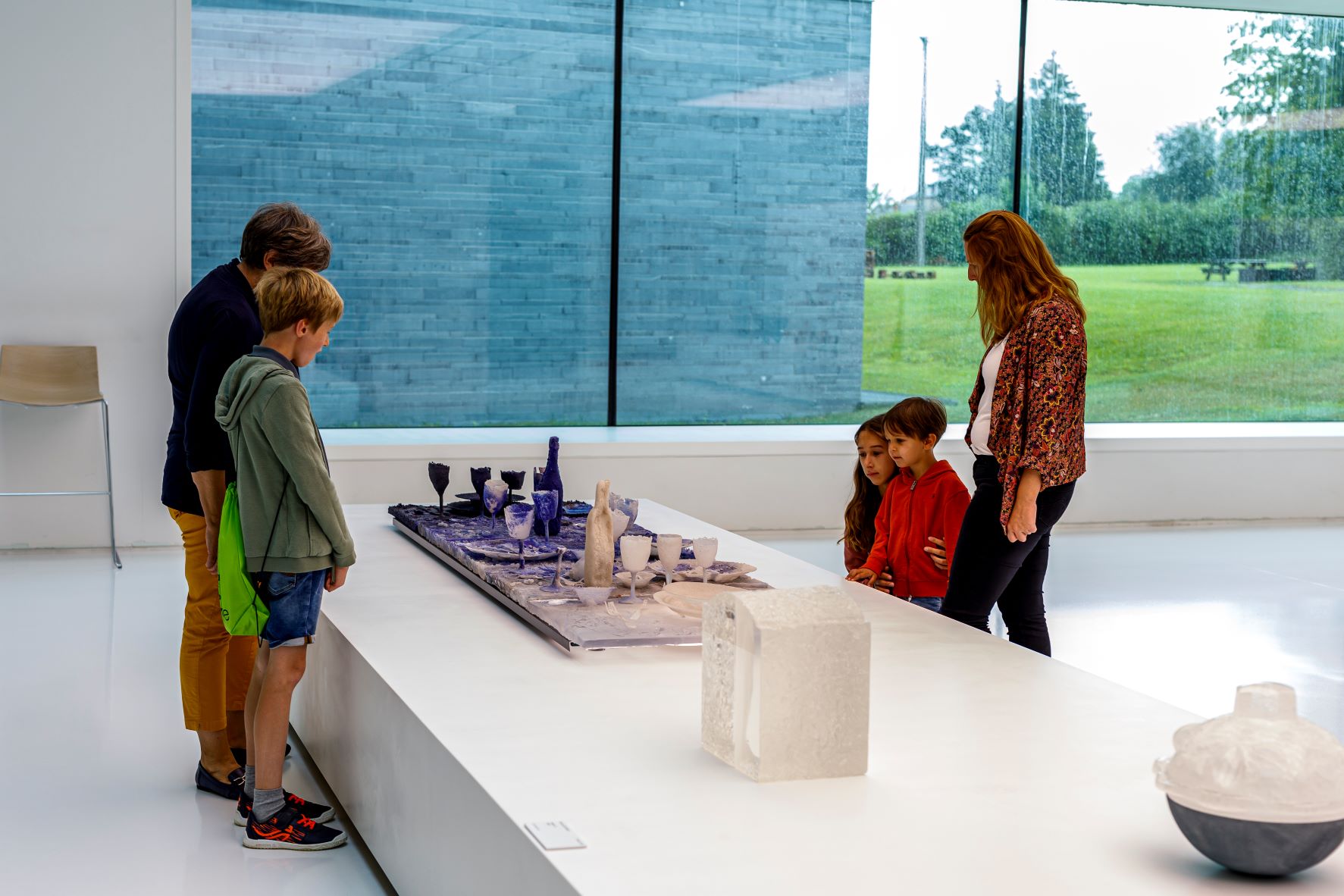

Exhibition at the MusVerre

The MusVerre suggests to revamp the cabinet of curiosities theme by exhibiting works, with a majority made of glass, exploring all sides of the naturalia, artificialia and even the famous monstruositez from the 16th century.

In complete opposition to the refined works usually exhibited in the MusVerre, the scenography is considered as immersive in order to surprise visitors and let their imaginary minds transport them.

As for every cabinet of curiosities, a classification is suggested:

The microscopic world

At a natural state, the diatoms, unicellular planktonic organisms, produce glass thanks to silica. From this surprising discovery, we propose works from contemporary artists, either for the use of diatom glass (Stéphane Rivoal and Lucile Viaud), or for the representation of cells (Anne-Lise Riond-Sibony) or because they exaggeratedly make viruses look bigger (Bernd Weinmayer)…

Under the ocean

In the 19th century, Léopold and Rudolf Blaschka, two Czech glass-makers, used a blowtorch to make hundreds of very realistic biological models. Their invertebrate marines were, for instance, sold to museums, aquariums and universities to be used as study models.

Nowadays, the marine environment still fascinates artists who try to reproduce the abyss magic (Yves Chaudouet), create sea monsters (Jaromir Rybak) or classify their works by themselves in the style of a cabinet of curiosities (Steffen Dam)…

Glass herbarium

The classification of plant species has always been at the heart of curiosity collectors’ preoccupations. The creation of the Royal Garden of Medicinal plants in the 17th century stimulated plant research as well as their preservation.

We propose artists using plant material as their source of inspiration (Julie Gonce), others representing plants in a really realistic way (Dafna Kaffeman) but also artists depicting nature in a subtle and poetic way (Iris Haschek) or in an excessive way (Jason Gamrath).

Artistic entomology

As for plants, collectors of days gone by tried to classify the insect kingdom and kept loads of specimens, which is still the case in Natural History Museums.

Contemporary artists take this entomological world over, in a poetic way (Judi Harvest), a playful way (Jan Fabre) or a disturbing way (Rose Wylie).

Fantastic menagerie

In the 16th century, many curiosity collectors used to get only a single piece from distant animals (a tooth…). Their imagination then flied to picture an animal in its entirety: that is how narwhal defense would commonly become the unicorn horn.

The hybridization of shapes in contemporary art brings artists to reinvest in those fantastic creatures: some work from naturalized animals (Julien Salaud, Kohei Nawa), others reify eggs (Othoniel), and others focus on the hybridization between species (Koen Vanmechelen).

Human productions

Thanks to the development of distant explorations from the 17th century, curiosity collectors could satisfy their desire of artificialia by ordering new objects directly to the travelers: weapons, currencies, furniture… In addition, scientific machines, automaton or ancient objects also aroused their interests.

This section would enable MusVerre objects from the ancient collection to be exhibited: glass swords, barometer but also from the contemporary collection (Julius Weiland). Furthermore, many artists create bizarre objects which would perfectly fit in: glass armor by Patrick Neu, giant eyes made of glass by Vincent Breed…

Vanities

The Kiosque will be dedicated to the notion of vanity, which evokes in a symbolic way the mortal destiny of human beings and makes people think about the frivolity of the world pleasures. As they became a painting genre in their own right in the 16th century, those still-life paintings would often fit in the cabinets of curiosities of European collectors.

Following the two World Wars, contemporary artists tackled the question of the vacuity of existence and reinvested in the vanity theme.

Under the Kiosque, a vanity borrowed from the Flandres museum in Cassel could communicate with a still-life painting by Eliott Walker, a glass skeleton by Adel Abdessemed, or even a skull by Jan Fabre.

Pharmacopeia

The space of the Echappée could be used for the exceptional presentation of a set coming from the Heuclin pharmacy.

This pharmacy was built in Sars-Poteries in 1898 by Thémir Heuclin (a glass-maker descendant). The pharmacy set of jars made of blue glass, with tags made of porcelain and showing scientific names which are sometimes mysterious, takes us back to another time.