Out with the old

Throughout her long career in architectural glass design, Catrin Jones has sought to educate her clients on the varied possibilities of contemporary glass and use of the latest technologies. Linda Banks finds out more.

You are recognised for your architectural glass work. What originally led you to start working with glass?

I studied for a Foundation at Swansea School of Art in Wales, where we had a very good fine art tutor who really made me start to think about what art can be. At age 18, I didn’t think I had much to say, so the idea of pursuing a meaningful career in fine art seemed out of reach. After a lot of meandering, I started to look at formal patterns and the notion of re-creating them in three dimensions using intricately cut out and interlocking shapes in perspex, which got me thinking about colour and form. This led me to study jewellery, where I was a lone student in a basement room working my way through the college’s supply of hack saw blades. I would gravitate upstairs to the stained glass department for some relief from the frustrations of attempting to make tiny things, to a world of light and pure colour.

It was a revelation of sorts. I, like lots of people, only knew of stained glass in its traditional format or as a Victorian door panel. I was not interested in this at all. But there, in an upstairs corridor of an old art college in Wales, I saw the unbridled power that pure transmitted colour can have on an interior. Embers were lit.

Although I initially thought that I would like to work in three dimensions with hot glass in order to continue with the pattern work I had begun on the Foundation course, the more research I did on the contemporary glass work being done in Europe and America, the more I wanted to try stained glass. The only problem was that the course was in Swansea, my home town, and I wanted to be elsewhere. At that time, the course was a magnet for many international students and it was headed by a staunch Welshman – an interesting mix. I soon realised that the world was coming to Swansea, which dampened my desire to leave town, and my enthusiasm for glass took over.

What glass techniques have you used and which do you prefer?

I’ve worked with stained glass, if you count my years in college, since 1979, so I reckon I have knowledge of nearly every technique there is. This is not to say I am good at all of them. I’m not a great glass painter, and I’m not really interested in pursuing realism in glass. To me, it’s a chance to expand. I was always on a mission not to repeat the past, which, as I began trying to make a living doing my own contemporary work, seemed like a yoke. I was forever trying to inform clients about design and the importance of commissioning work that is contemporary. That said, when I set up my own studio, five years after setting up a co-operative studio with fellow ex-Swansea students, I only had an acid etching facility and no kiln, so that is what I focused on. I don’t think you need to know every single glass technique, but it’s useful if you know someone who does!

What is your creative approach when designing for large-scale projects?

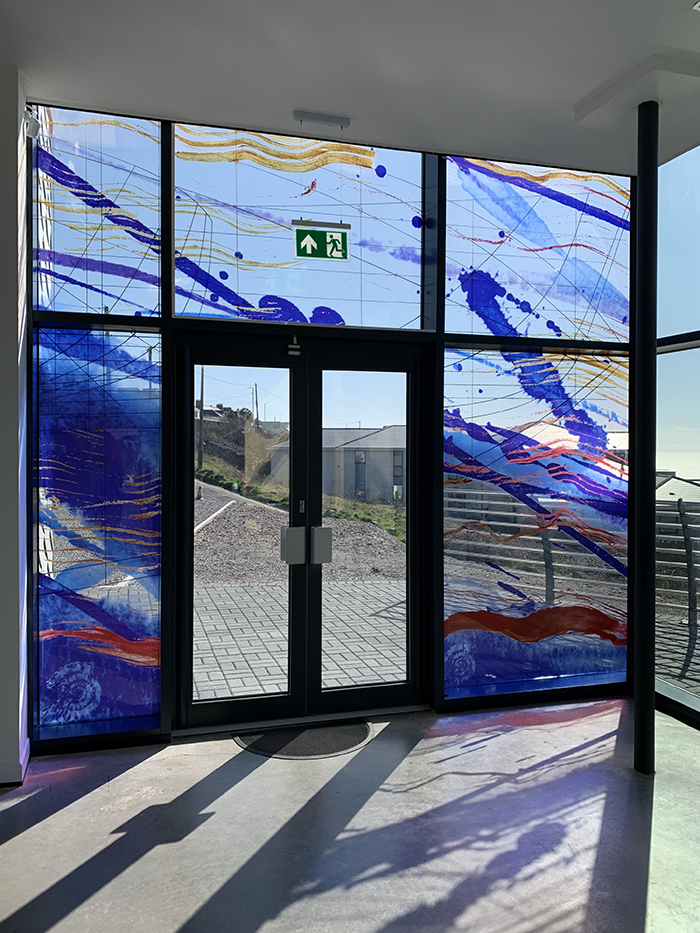

My early public art commissions allowed me to go to Germany and France to have colours made for each specific commission. I kept the lead line to a minimum and worked on the largest pieces of double flash glass that I could get into my acid tank (almost full sheet size). I tended to make my own rules; as I didn’t want to stand over an acid bay for long periods of time, I’d leave the glass alone to etch slowly, and got some great results that way. I loved the effect that was achieved, as it was painterly and also slightly serendipitous. Each piece of glass always seemed to have its own direction, and I enjoy working with surprises. I also felt that there was a lot of development happening from the design phase when working with the glass itself, which I relish. It is such a different story when designs are translated by a studio and by a different hand. Broadly speaking, I think of techniques as tools, so it’s about fitting the right technique to translate the design adequately.

When working to scale, there are a number of constraints – sometimes budget driven and sometimes to do with the glazing system. I try to be open-minded about how best to translate something in the beginning. It’s all about getting the best results for what one is trying to achieve. I’m usually very clear, but sampling is key and I often try out a wild card to push the boundaries. I hate seeing glass commissions that are advertised as requiring an artist to have no previous experience with glass, as if it’s all left to the studio to realise a vision. There are too many examples of this, which breaks my heart to be honest. Because glass is bright and shiny, a lot can be carried by these characteristics, which should not mask bad design.

I’ve always aspired to working on a large scale, because seeing the works of the great German masters, and medieval masterpieces like those at Chartres and Saint Chapelle is awe-inspiring. Architectural glass has always been, and remains, underutilised. So my approach is ‘the bigger the better’, even though I rarely get the chance to work on a truly impressive scale. The building, the light, the glazing system, the budget, the client and what I can achieve within these boundaries have all to be considered. I tread a careful line between listening to the requirements of the client and pursuing my own creative journey. I think we have an important role to educate and lead the client in order to make good work. It’s a relationship, and I always explain at the outset that I’m unlikely to be hemmed in by the initial brief.

When I’m working on public commissions, there’s always a lot of initial research; historical, geographical, photographic. I make drawings and take photographs. I’ll spend some time in the place itself. I sit on it all for as long as I can, so that all the obvious responses are out of the way, and then see what surfaces. I try not to start out with any preconceptions, as I see each piece as a new beginning and I do not want a piece to look like something I’ve done before. It’s important for me that there is a strong narrative to the work, that it is of its place and time, and that it operates on many levels.

What are the challenges when working on public commissions and how do you overcome them?

I suppose that each commission comes with a new set of challenges, but this is the nature of any project. I enjoy the process of problem solving. These days, the challenges are mostly budget related – ever more work is required for diminishing returns. This, in turn, can also lead to new ways of doing things technically, so every cloud has a silver lining. It’simportant to have an open mind and not to make assumptions. Good communication is vital. Having a lot of experience really heIps to foresee difficulties, especially when working with the construction industry, which has changed a lot over my career. I’m not afraid to ask questions and to say when I do not know all the answers. I work with some great studios that help the big things happen. Their technical knowledge is often critical to a successful outcome. I’ve been working with David Porto since 1994 and he’s been invaluable in this process.

Do you have message(s) you want to convey through your art, or are you constrained by the ideas of the client?

There’s always a narrative in my work and, rather than letting the ideas of a client act as a constraint, I’ll always seek to work with the client to find unexpected ground for both parties. It’s important that we artists have the confidence to educate a client, and not to be in a position where the work is compromised creatively.

What is your favourite tool or piece of equipment and why?

My favourite tool is my sketch book. It’s where all my work starts, with observation and time spent looking, thinking, recording. These are not finished works, they are to do with the thought process, and a way to capture immediacy. They are messy and playful recordings, where anything can happen. I also take a lot of photographs. These act as back up and as notation for ideas, which I often reference later on in my work.

Do you have a favourite piece you have made? Why is it your favourite?

I’d say that my next piece of work is my favourite. I’m self-critical, so there’s always something I’d do differently next time round, which is what keeps me going, and is what is endlessly fascinating about the challenges of working with glass. There is always something new to learn.

How has your practice evolved since you started? Have you embraced new techniques?

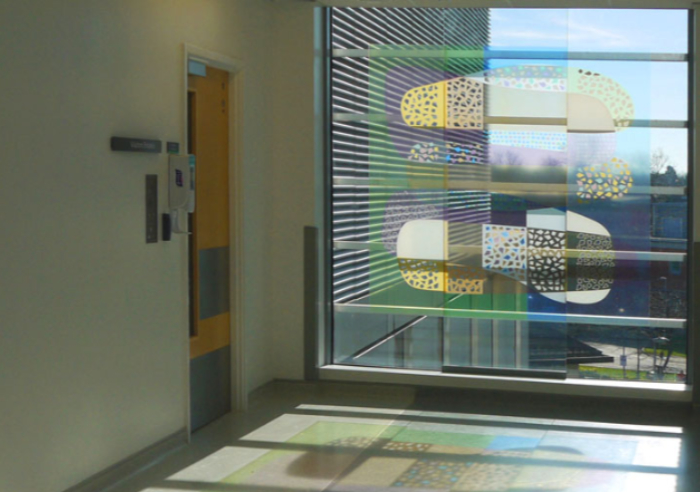

My practice has changed with technical innovation. When I started out, I was using the biggest pieces of mouth-blown glass I could, and they were leaded together in the traditional way. These days, I seldom have a budget that allows this, and leaded panels may not be considered safe enough for public spaces. We always try to do as much as is technically possible within the budget, which used to be a matter of using screen-printed colour rather than mouth-blown glass. Now, I could be using digitally-printed enamels or films. I’m aways looking for ways to animate the surface as much as is appropriate so, lately, I’ve been combining printed techniques with silver details and dichroic foils. Where I have a double-glazed unit or laminated glass, I’ve been working on three faces of glass, to build up interest and depth.

Where is your glass practice heading next?

I’m not sure. I like to stay open-minded, and I’m happy if I’m lucky enough to have a commission to work on. In my dreams I would be making ever-larger projects and championing my first love of beautiful, mouth-blown glass…Commissions welcomed!

These days, my work is focused not only on glass, but on therapeutic environments as a whole, and I try to to focus on colour and the ambience of an interior in its totality. I’ve also been working with cast concrete on a public art project and I would love to develop into creating three-dimensional artworks. It can be a case of chicken and egg in the world of public art, though, and if you do not have a piece of sculpture in your portfolio, it’s difficult to gain a commission in this direction. I shall keep trying!

And finally…

It’s been very sad to see how our amazing glass courses have been shut down. It displays a real lack of respect for the skills they encompassed and is troublingly shortsighted. I benefited, like many others, from a brilliant education, taught by practising glass masters and artists, which has enabled me to continue working solely as an artist. I am lucky to have had this good fortune. But what of the future? I am happy to share my skills and experience and to do what I can to support emerging artists, and to champion our medium. I also lament the lack of any critical discourse about glass. There have been several really good conferences about architectural glass, with many artists coming together to talk about their work and share experiences. Time for a bit more of that perhaps?

About the artist

Catrin Jones is a Welsh artist with an international reputation. She realised her natural aptitude for drawing early on, which determined her career as an artist. She trained in architectural stained glass at Swansea School of Art and, in her early years of study, won a number of glass prizes, leading to the purchase of an experimental panel by the Victoria and Albert Museum. She was also commissioned to make works for local churches and residences.

On graduating with distinction, in 1982, she and five fellow ex-students established Glasslight Studios, a co-operative stained glass studio in Swansea, where patronage from the Catholic church resulted in a variety of ecclesiastical commissions. Since 1987, Catrin has pursued an independent career as an artist, specialising in glass for public buildings and architectural settings.

She has completed many commissions in public buildings and religious environments. She has exhibited in Europe, Japan, Australia, Canada and the US, and her work is also included in public collections in the UK, North America and Japan.

In 2023, the artworks at Grange University Hospital, Gwent, won the Dewi-Prys Thomas award for good design, including five waiting room glass screens designed by Catrin.

Find out more via the website: https://www.catrinjones.co.uk/

Main feature image: Glass installation at Grange Hospital. Photo: Phillip Roberts.