Norwood Viviano’s glass work investigates the effects of industry and population shifts on the landscape over time. He uses digital 3D computer modelling and printing technology, alongside glass blowing and glass casting processes, to create his micro models of these macro changes. Glass Network digital’s editor, Linda Banks, finds out more.

What led you to start working with glass?

I have an undergraduate degree in Glass and Sculpture from Alfred University. Initially, it was the community and comradery of the hot shop that drew me to glass. I loved working with people to share in the creative process of making work. While I don’t always work in hot glass now, it’s the strong and supportive glass community that keeps me engaged with the material. I could also add that glass is unlike any other material. It certainly has its challenges, but rewards you with what it does with transparency, light, and colour.

What glass techniques have you used in your career and why do you have a preference for cast glass today?

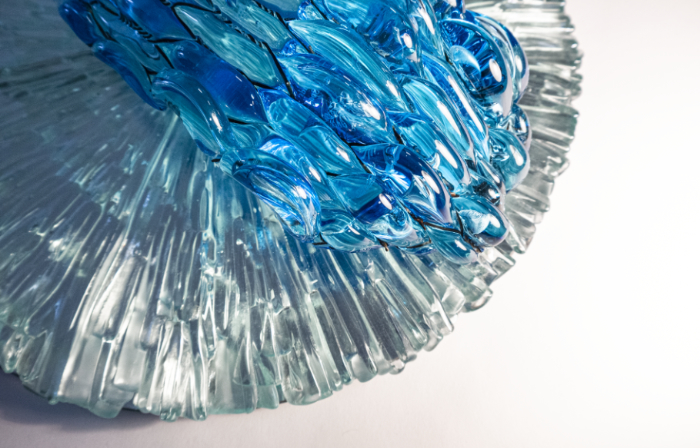

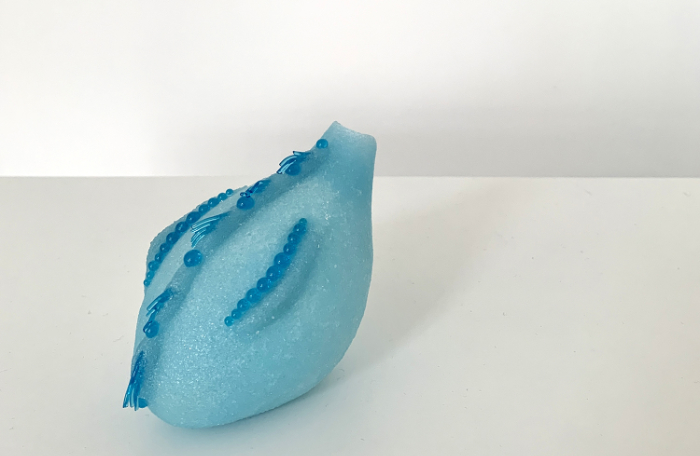

I’ve spent my career working with multiple materials and processes, including glass. This includes metal fabrication, bronze casting, and digital fabrication. However, in the last 10 years, I’ve primarily split my time between working in hot glass and kiln cast glass. I’m drawn to working in glass by both the beauty of the material and the challenges of working it. Kiln cast glass affords me several opportunities to combine content or ideas and shapes together. I find the mould making process affords me several steps to consider how ideas will develop and play out within a piece.

Can you tell us something about how you developed your working methods? How did you come to combine digital 3D computer modelling and printing techniques with glass blowing and casting?

I’ve been teaching digital 3D modelling and 3D printing for nearly 20 years. I was drawn to working with this new technology early on by the accuracy and aesthetic.

I’ve always enjoyed the process of making moulds. These processes are now deeply embedded in manufacturing and foundry practices. Therefore, it was a fairly natural progression to working with the 3D computer modelling and printing techniques with glass – especially for someone who has a focus on casting.

In addition to 3D computer modelling and printing techniques with glass, I also use LiDar 3wd scan data. Essentially, this is a 3D laser scan of the Earth, which provides a 3D model or snapshot of the landscape. The LiDar can be converted into a file for 3D printing, which, in turn, can be kiln cast in glass.

What is your favourite tool or piece of equipment and why?

There’s so many. I would initially say my hands, my brain, and my computer.

Beyond those, I have new Paragon Ovation kiln that’s been a good addition to my studio. It’s deeper than my other kilns, at nearly 57cm. This kiln gives me the opportunity to work deeper or create more complex pieces. It’s been a game changer and perfect for when I developed work for the new Recast Cities exhibition.

What messages do you want to covey to your audience through your glass work, such as the Recast Citiesseries or the Cities Underwater project?

The following direct quote from Sarah Darro’s essay for the Recast Cities exhibition, at Heller Gallery in New York, is a good answer:

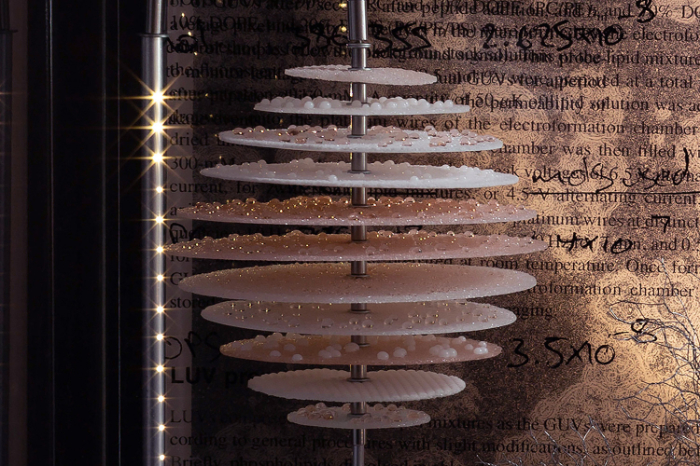

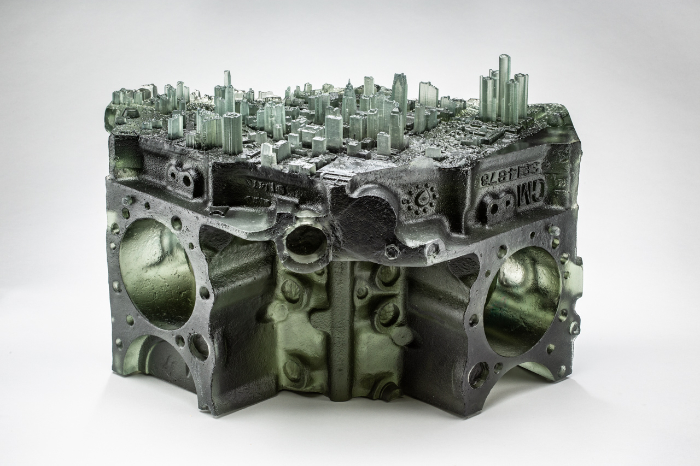

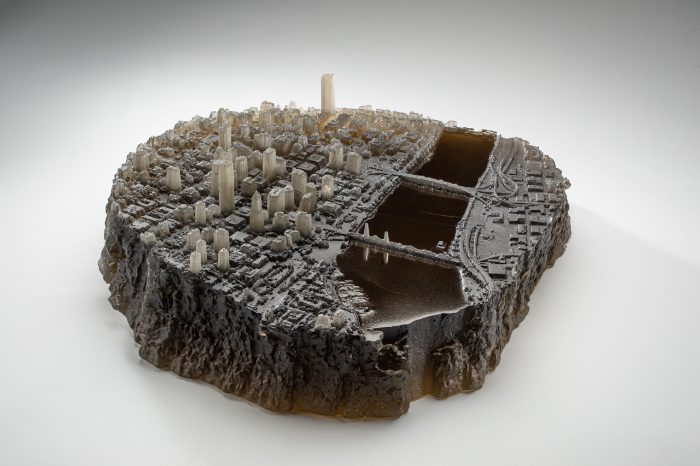

“Recast Cities merges urban landscapes with the symbols of industry that have fueled their booms, busts, and builds. A gleaming combustion engine fuses with the bustling metropolis of Detroit. A set of Libbey Hobstar glasses support a hole-punched Toledo skyline. An undulating tree stump contains downtown Portland. A steel I-beam bolsters the golden triangle of Pittsburgh and its forked waterways. Manhattan’s imposing, iconic skyline rises out of a stack of newspapers. Norwood Viviano’s latest series is a lyrical, surrealist departure from the distilled aesthetic of data visualization that has come to define his oeuvre. It extends his decades-long conceptual project of charting change in cities and populations wrought by industry over time but encodes the works with newfound self-reflexivity. The nebulous boundaries between the objects at the base of the sculptures and maps at their surfaces make the viewer critically aware of the constructed nature of cartographic space, while the story of American industrialization told through each of his chosen cities is also materially embodied by the works, which are themselves made from technologies, processes, and materials born out of those industries.”

Do you have a favourite piece you have made? Why is it your favourite?

In the Recast series, ‘Recasting Detroit’ stands out. Not only was it the first experiment that led to a new, larger body of work, but it also pushed me to learn a lot more about kiln casting. It’s also a bridge piece between my older Mining Industries kiln cast glass series and the new Recast series. I made this piece while working as a fellow at Wheaton Arts in Milleville, New Jersey. Recasting Detroit started out purely as an experiment and turned into a solo exhibition four years later. Over the last decade, residencies and fellowships have given me the time to experiment and explore new ideas.

Where do you show and sell your work?

For the last 10 years, my primary dealer has been Heller Gallery, New York, NY. I recently opened my fourth solo exhibition there in March 2021. My work can also be found in the collections of the Corning Museum of Glass, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Shanghai Museum of Glass, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery.

Do you have a career highlight?

The four-person invitational exhibition at the Smithsonian Renwick Gallery in 2016 was a career highlight. Not only was my work shown alongside that of other incredible artists, but it gave my work the broadest audience to date. This exhibit was a springboard for several opportunities since.

Having Global Cities acquired by the Corning Museum of Glass was a career highlight as well. When I was a student at Alfred University, I visited Corning several times a year, drawn by the quality of the collection and the fact that it was only a one-hour drive away. When this project was acquired, it was hard to believe that my work stood up to the strength and quality of the other pieces in the museum.

Who or what inspires you?

Landscape and people always amaze me. Much of my work explores the landscape in some way, but it’s so much about how people influence and change the landscape. For the last 10 years, my work documents the power dynamic between industry and community and how it played out over time.

How has the coronavirus pandemic impacted your practice?

The pandemic was challenging in so many ways. I’m very fortunate that I haven’t known many people who were sick with Covid. I was prepping for my solo exhibition at Heller Gallery as the pandemic hit. Making work, having assistants in my studio, and sourcing materials was pretty challenging. The pandemic forced me to be resourceful and try some new ways of thinking about processes. Early on in the pandemic, I had to develop work on a smaller scale so that I could handle it myself. I also had to reorganise tasks for my studio assistants to do without being in the same physical space. In the end, I’ve felt more productive during the pandemic, but it has made me rethink a lot my process and strategies for working with glass.

About the artist

Norwood Viviano received a BFA from Alfred University and an MFA in Sculpture from the Cranbrook Academy of Art.

He is an Associate Professor and Sculpture Program Coordinator at Grand Valley State University.

Work from his installation ‘Cities: Departure & Deviation’ was shown at the 2014 Architecture Biennale in Venice. In 2015, he had a solo exhibition at the Grand Rapids Art Museum and his work was included in the MFA Boston exhibition Crafted: Object in Flux. In 2016, he had a solo exhibit at the Chrysler Museum of Art and his art was included in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery exhibition, Visions and Revisions: Renwick Invitational.

His pieces are held in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; DeYoung Museum, San Francisco, CA; Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY; Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague; John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI; and the Museum of Glass, Tacoma, WA, as well as in private collections.

Find out more about Norwood Viviano and his work via his website.

Photographs: All professional images by Tim Thayer/Robert Hensleigh. Process images by Norwood Viviano. Main feature image: ‘Recasting Detroit’ by Norwood Viviano.