Phil Vickery was captivated by a glassblowing demonstration he saw as a boy, but it was not until he took a glass module during his art foundation course that he decided to pursue this rather than painting as a career. Linda Banks finds out more.

What led you to start working with glass?

I knew I wanted to be an artist from a very young age, but I couldn’t imagine where that would lead me! At the age of about eight, I went to the Isle of Wight and visited some glass studios there. I was amazed! I couldn’t stop watching the glassmaker blowing glass. There was so much action and beautiful fluid motion to what they were doing.

But, back then, I was still interested in painting. My direction changed when I went to Portsmouth University to do my foundation in art. They had a module in glass. I took it because I remembered my time watching glass blowing at the Isle of Wight and I was interested in painting on glass. I was intrigued by the way glass bent the light and distorted what was behind it, so the lecturer suggested doing the module. I was hooked right away! This led me to Wolverhampton University to study glass. As soon as I got in the hot shop I told my then lecturer, Colin Rennie, that this was all I wanted to do! And it was!

What glass techniques have you used and which do you prefer?

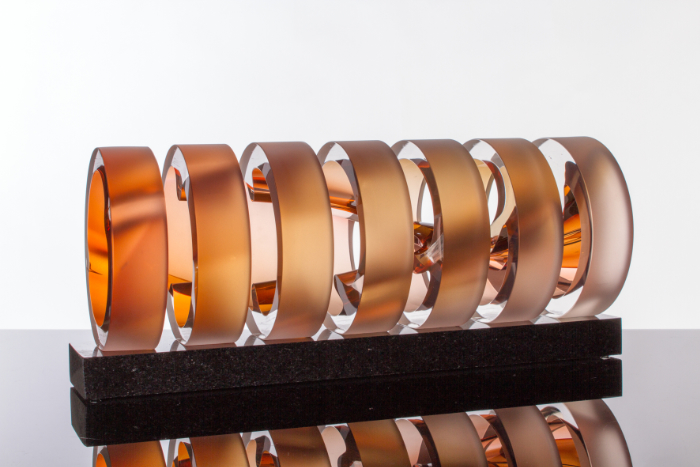

The techniques that I have used most are hot glass and cold glass. However, I have dabbled in kiln work, and I am interested in experimenting with copper plating. When I started, I was only interested in the hot glass process and I did everything that I could to not have to cold work my pieces! But, as time and my career progressed, I integrated cold working into my design ethos. It is now almost more important in my work than the hot glass.

What is your creative approach? Do you draw your ideas out or dive straight in with the materials?

Initially, I designed works to form ranges. I imagined them in a sketchbook and then set to realising those ideas in the hot shop. Later, my work moved away from ranges and giftware to one-off sculptures. I adopted a more evolving approach to my practice where the ideas flowed from one to another.

When I have an idea or theme that I want to explore, I think deeply about it to come up with a starting point. The piece is made in the hot shop, and then sculpted with cold working to the most appropriate form that demonstrates my theme. Cold working depends on the individual piece and seeking out where the colours and interior forms of the glass look amazing.

The post process work helps me to bring out the most aesthetically and conceptually pleasing glass forms to fit my mental image. Once the sculpture is finished I use the piece as a starting point for my next sculpture by studying it closely and looking at how it can be improved. The next piece is then informed by that design, so my process evolves with each creation. This is the way that I have built up a large body of work of predominantly unique sculptures.

What inspires your work?

The inspiration for most of my work is the beauty, and sublime ideas of deep time captured in lifeforms in the world’s seas. Most of my life I have lived by the sea, and its constant changing and beautiful variety havealways kept me captivated.

I am always driven towards expressing the inner self as well. I use my glass forms to explore complex theories of the mind. What is consciousness? These sculptures are a representation of the way people can think in an ephemeral way, and they also explore the flow of thought. Thoughts can flow from the subconscious like the way water can flow in a river.

What message(s) do you want to convey through your art?

My hope is that people can take what they enjoy from my work. It’s quite open to interpretation, so it can be anything the audience takes from the work, be it beauty, a feeling of the sea, or the internal, or something I didn’t even consider. It’s purposely left up to the viewer.

Aesthetic beauty plays a huge part in my work. I use abstract expression to grow my visual language. I utilise art to create representational, tangible artworks about the natural power of thought, relationships and human nature, as well as investigating how the subconscious is woven into this equation.

My sculptures are tools of representational awareness; a focusing of human energy, to convey thoughts. I employ my own subconscious as a powerful lens to focus my own individuality and use the art to explore what connects us as a species. In my sculptures, colour and form represent various emotional states of the mind and the subconscious. I strive to realise this idea with my own forms of symbolism and representation.

What is your favourite tool or piece of equipment and why?

I have two different things, one from each of my preferred techniques. My jacks from Ivan Smith are my best hot glass tools! They are my favourites as they are the best tools in the world, and they are no longer available as the maker died. Early on in my professional life, I had the pleasure of travelling to see Ivan in person to commission the tools and he even drew around my hands to custom fit them personally to me!

My favourite piece of equipment from cold working is my relatively new diamond flatbed. This was imported from His Glassworks in America. It has made my practice much more professional as it polishes perfectly flat and true. It has provided an upgrade to my cold working, in effect.

Do you have a favourite piece you have made? Why is it your favourite?

I don’t have a specific piece that I could call my favourite, but I would say that some of the best sculptures that I have made are from the ‘Thoughts’ range. I feel that they have the most context and are the most contemporary. They have more substance to them, and I feel they are my best work.

Where do you show and sell your work?

I show my work mostly in galleries in the UK and around the world and I occasionally take part in glass exhibitions. In recent years the glass world seems to have shrunk, particularly in the UK, and so the places I show work have shrunk too.

What advice would you give to someone starting out on a career in glass?

My advice would be to get as much experience as possible, and just keep working at it!

Do you have a career highlight?

The highlight of my career was when I was chosen for one of five Honorary Diplomas of the Jutta Cuny – Franz Foundation, Germany, in 2011. A close second was when I was a winner and recipient of the Renwick Award for Distinction in Glass, from Washington DC, USA, in 2009.

Where is your glass practice heading next?

I hope to continue my glass practice in the North East of the UK, but things are not looking great. The place I hire to blow glass, the National Glass Centre (NGC), is soon to be closed down. Like many glass studios in the UK, they are finding it hard to keep going, mainly because of the huge expenses they incur for energy, and materials. Across the UK glass courses are closing down, too, so I do have my worries about the future of my business and the UK glass world in general, but I will do my best to keep going!

And finally…

If you want to support the campaign to save the NGC then please sign the petition here.

About the artist

Phil Vickery holds an honours degree in Glass Design (Major) and Photography (Minor) from the University of Wolverhampton. He gained a postgraduate qualification from the International Glass Centre, Brierley Hill: ‘Glass: Professional Development. Prof dev level 5’. While at Brierley Hill he won the Frederick Stuart memorial fund for ‘Best Blown Glass’. After this he won a scholarship residency at the Red House Glass Cone from 2002 to 2004.

In 2004-2005 he was an artist in residence at the Surrey Institute of Art and Design (Farnham University) where he taught basic glass blowing skills and assisted Colin Webster. While there he was sort-listed for the Glass Sellers Award, 2005.

In 2006 Phil achieved a Master of Arts; Glass with distinction at the University of Sunderland, where he became the artist in residence, and teaching assistant to Colin Rennie (UK), Jeffery Sarmiento (US), and Scott Chasling (AU).

He has won various awards for his glass work and in 2016 opened his own cold working studio in Sunderland with his partner.

Find out more about Phil Vickery and his work via his website, Facebook or Instagram: @philvickeryglass

You can also watch him at work on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3rXRf60H2XA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qc13dTAHjgc

Main image: ‘Transient Thoughts’ in a yellow and green colour way.

All photos used in this article by Jo Howell.