Dutch glass artist Bibi Smit is inspired by natural forms and loves to develop her ideas through varying pattern and colour. Linda Banks finds out more.

What led you to start working with glass?

I was a Foundation student in Farnham, at the West Surrey College of Art and Design. I decided to move to England and study there. During my introductory year, I spent a long time watching other people work with glass and I became very interested in the material. I saw the glass as a fluid, moving, living material that could be used to create art. I was fascinated and felt that it was a material of expression. There seemed to be a link between watercolour painting and glass. The transparency and light colour of each layer was like water colouring with glass.

What glass techniques have you used in your career and why do you prefer those you use today?

I like the immediacy of working with glass. I like sandcasting and glassblowing. In sandcasting, you ladle the hot glass out of the pot and pour it into a sand mould. The resulting pieces are very nice, heavy objects made of glass.

I like being close to the glass. When you are blowing, you are physically close to it. You are breathing into it; you are touching it with the tools. It is a more intimate relationship. When I am working with hot glass, I have a connection with the material and I see how it moves.

But I also feel the same connection when I am cutting and polishing, because it is a nice contrast with the hot glass. It has a meditative quality that allows me to contemplate the pieces. It’s more relaxed and ‘Zen’. I find it really calming because it is so different. I enjoy combining hot and cold techniques to achieve the shape that I want.

Can you tell us something about how you developed your working methods? Do you draw your designs out or dive straight in with the materials?

I prefer to make something small with the material. I work out the dimensions and the process in a small scale. I may do colour tests and draw to get the proportions right, but I would rather do it hot. Drawing and working with hot glass are processes with very different natures.

Who or what inspires you?

I feel inspired by nature; the way the wind moves the waves and the trees, the way birds fly through the sky. I feel inspired by architecture and shapes.

I am also inspired by the people who taught me how to work with glass, such as David Kaplan and Annica Sandstrom at Lindean Mill Glass in Scotland, and Willem Heesen at De Oude Horn in Leerdam, where I started out as a glass assistant. I had a lot of freedom to use the furnaces and develop my own work, to do the hours and make the mistakes that allowed my work to develop. I think mostly I am inspired by their working thoughts, their commitment to the material, attention to details and by the way they set up the workshops.

What is your favourite tool or piece of equipment and why?

My metal ladles are one of my favourites because they give me a strong feeling when I am stretching the glass. I feel through the material and the tools become my hands and fingers.

Gravity as a tool is also very important; there is so much behind understanding how glass moves. I also love the smell of some of my brushes, like The Barcelona, my grass brush from Spain. It has an amazing smell when I use it on the glass. I buy different brushes and new, small tools for my workshop wherever I go. When I find something new that I haven’t used before I find it really exciting.

A lot of your work is very organic. What message(s) do you want to covey to your audience through your art?

I think art creates happiness. Some people have an emotional connection with pieces because they convey a feeling or a story. I grow relationships with the things that surround me. Some came from the forest, some from my parents’ house, others from the unknown. They all tell a story. Glass is the same for me; it carries something to be said and a soul. The organic, the natural forms, the wind, the softness of the shapes – they all carry a sensibility that mirrors how we look at nature and find energy through both nature and art.

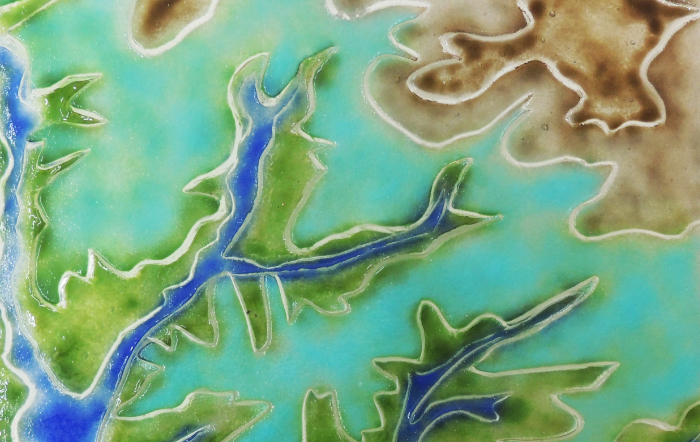

You are exhibiting ‘Clouds’ as part of ‘Masterly – the Dutch in Milan’ in Italy this September. How and why did you develop this installation?

The original idea was inspired by a painting called ‘Huis ten Bosch’, by Jan ten Compe. I decided to look at the clouds of the Dutch masters, the painters of the Golden Age, and their big skies in the landscape. The clouds have a softness, which glass also has.

I kept making more pieces, because I saw another colour that I wanted to try out and translate into glass. And I wanted to make an installation that was bigger than the audience – where you have to walk around and become part of it. It needed to have a certain size to achieve the idea of being in a space where you can forget about everything else. The audience would be embraced by the installation.

I think it’s hard to get everything right in one piece: the colour, the shape, the build-up, the thickness, timing and gravity all need to be right. There are only a few seconds to make decisions with glass and you change with them. Each piece brought me a step closer to what I was envisioning. The installation is an ode to the power of nature.

Do you have a favourite piece you have made? Why is it your favourite?

For me, it’s mostly the piece that I am working on. It has a sense of temporality. I made a crinkle vase a few years ago and I took a picture of it to remember it. Later on, this idea was developed into the ‘Crinkle’ glasses. I like the sense that I have a piece that doesn’t look good, but I know it has something that I want to develop further and I don’t know what that is yet. I have some of these pieces sitting on shelf, waiting for the right moment. I find that very exciting.

And thinking back, the first ‘Swarm’ I made marked a very special moment in my work, because I made so many elements and created something bigger. In this way I started working with installations. I had the excitement of making so many different elements and levels that allowed me to create the movement I was looking for.

Where do you show and sell your work?

Currently, I am showing my work at De Kliuw Gallery, Bonnard Gallery and Wilms Gallery in the Netherlands. I also sell my work at the Mint Shop in London and Haven Palm Beach in Florida. And I host exhibitions in my studio and gallery, in Loosdrecht, by appointment.

This autumn I will also be participating in the Masterly Dutch Pavilion part of the Salone de Mobile in Milan (5-10 September), Venice Glass Week in Venice (4-12 September), Masterly the Hague (21-24 October), and National Glass Centre Prize in Sutherland (October 2021-March 2022).

Do you have a career highlight?

I think receiving recognition for my work has been a very important part of my career. There are moments when I have received a nice critique of my work and sometimes people tell me they have felt a connection with the object; they felt something spoke to them. That is very important to me.

How has the coronavirus impacted your practice?

Initially, having a glass workshop gave me the freedom to keep creating and making, even when I was there by myself. I made a limited series of drinking glasses in that time. It was just me in the studio with the furnace on. So, in my case it just gave me space to make and blow glass, for a few weeks.

About the artist

Bibi Smit (b. 1965) is a Dutch glass artist and designer, living and working in the Netherlands. Her work explores the patterns, rhythms, colours and movement of natural phenomena.

Smit was a glassblowing assistant to Willem Heesen (NL) and trained with David Kaplan at Lindean Mill Glass (UK).

Since the 1990s, she has shown at national and international exhibitions, including national glass museums and the Salone del Mobile in Milan. She attended a workshop with Boyd Sugiki at Pilchuck Glass School (USA) and has lectured at the Edinburgh College of Art and Sunderland University, as well as other glass centres in Europe. She is an active member of the Glass Art Society (USA).

In 2019, the documentary ‘Moving Glass’ was selected for the North Lands Creative Film Festival. The Glassmaker episode from the World of Calm series, streaming at HBO Max, is a poetic narrative of her work and the power of nature.

Public collections: National Museums of Scotland (UK), Nationaal Glass Museum (NL), Museum Jan (NL), Glassmuseum Lednické Rovne (SK), Collection North Lands Creative Glass (UK), Museum für Glaskunst (DE) and the Glasmuseum Alter Hof Herding, Ernsting- Stiftung (DE).

Find out more via her website: www.bibismit.nl or visit Milan for the 59th edition of Salone del Mobile, where Bibi Smit will present for the fifth year in a row. Here, from 5-10 September 2021, the ‘Clouds’ installation will be shown as part of ‘Masterly – The Dutch in Milan’.

Main feature image: Detail from ‘Clouds’ by Bibi Smit. Photo: Frieda Mellema.